Hello readers! Thought I’d try something different again today (nothing like a bit of consistency to keep the audience engaged). You might have noticed that the title utilises an arbitrary amount of time in order to attain alliterative flow, from which it is embarrassingly obvious that I needed a snappy name for a new type of blog post. Six-minute summary? The logic is simple: I’d like to wax lyrical about interesting people and places every now and then – and I’ll try not to waste more than six minutes of your time.

Alfred Wegener

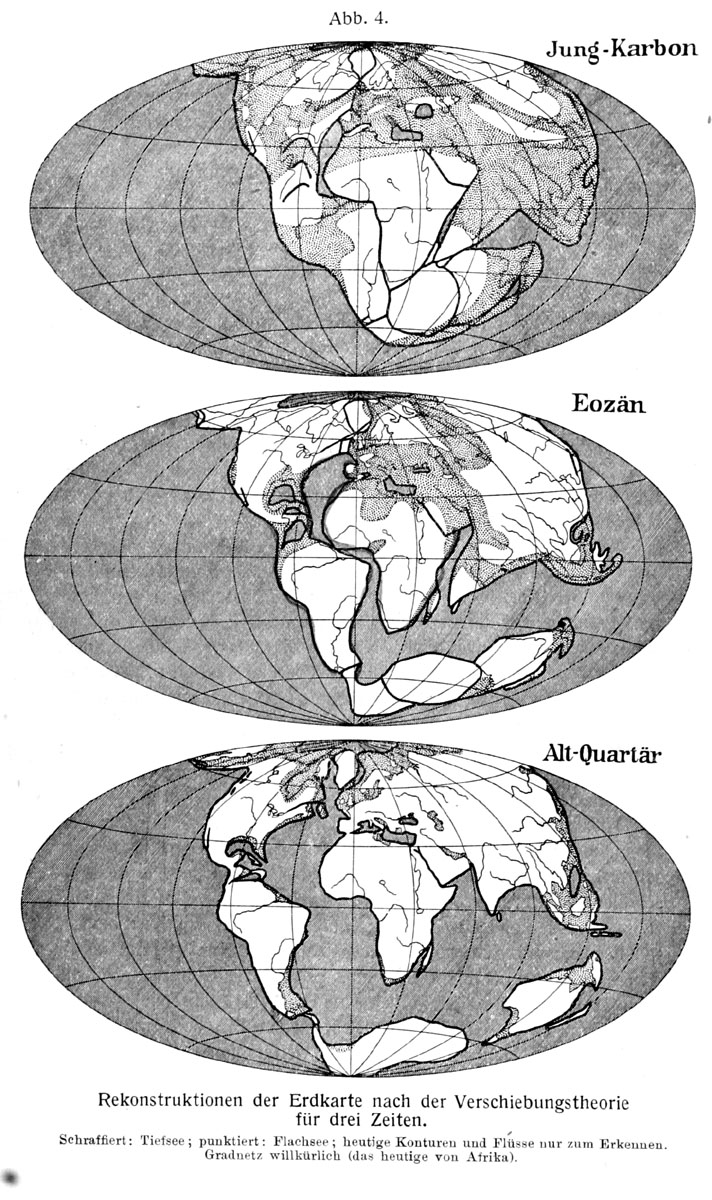

You’ve probably heard of Alfred Wegener. If you haven’t, then I’m sorry for belittling you in such a brutally disingenuous manner. Alfred Wegener is famous for coming up with the theory of continental drift, only to have his ideas laughed at by most contemporary geologists. By the time evidence started piling up in Wegener’s favour, he had suffered the unfortunate setback of dying in Greenland, and so he never knew that his work paved the way for a paradigm shift in the Earth sciences.

Today we’ll look at the history of Alfred Wegener, to understand how he came up with such a ground-breaking idea (pun intended?), and why the scientific community was so reluctant to accept it. We’ll even get a little philosophical, and wonder about the nature of scientific paradigms, what it means to be confined by existing ideas, and the terror of foundational science being overturned by something new and better.

99 Red Weather Balloons (a tenuous reference, apologies)

Alfred Wegener was born in Berlin in 1880. He then had an “early life”, the details of which can be found on Wikipedia. However, things started getting really interesting when he went to university, where he studied meteorology, physics and astronomy (but NOT geology – which might come as a surprise). He was more interested in what went on above him than below him; indeed, he and his brother pioneered the use of weather balloons to track air masses, and set a record for the longest continuous balloon flight – all without getting shot down or causing any major diplomatic incidents.

Wegener had a few close encounters with death before he actually died. In 1914 he was sent to the front lines in Belgium, although after being wounded twice in a few months, he was declared unfit for service. Instead, he was sent to join the army weather service, so you could argue that he dodged a bullet there (perhaps not literally). He faced much greater danger in his meteorological research, which took him to Greenland in a time before satellite communications or Gore-tex.

On Wegener’s first Greenland expedition, in 1906, two of his colleagues died. On his second expedition, in 1913, the team ran out of food and had to eat all their dogs and horses to survive. It was on his fourth expedition, in 1930, that he himself died. He had brought food to a camp of researchers, but there wasn’t enough for him to stay with them, and so he and his colleague left, only to perish in the harsh conditions.

But what does this have to do with continents?

It might seem odd that a meteorologist came up with an idea that would change geology forever – and maybe this goes some way towards explaining why geologists were so reluctant to accept it. According to Wegener’s book, The Origin of Continents and Oceans, the idea came to him in 1910, just from “considering a map of the world” and seeing the “congruence of the coastlines on either side of the Atlantic“. It wasn’t really his area, but something clearly drove him to dig a bit deeper – so he did.

According to him, in 1911 he “accidentally” came upon a report of palaeontological evidence for a land bridge between Brazil and Africa. Following this thread, he found a wealth of fossils shared between the two continents, very much suggesting that the two had once been joined.

Only one person before Wegener had suggested that continents could move: a man named Frank Taylor, who proposed in 1908 that the collisions of moving continents could uplift mountains. However, Wegener hadn’t read any of this work, so it seems that their ideas were concocted independently – making them coincidentally contemporaneous. Taylor, however, didn’t follow the idea much further, while Wegener definitely did.

So why did nobody like it?

This is an interesting question. For starters, Wegener’s idea might not have been dismissed as widely as we’re led to believe. Certainly, it caught the attention of many eminent geologists, including Arthur Holmes, and was quite popular in Europe by the 1930s. It was the Americans who seemed more reluctant to consider the possibility – and part of this may have been down to Wegener being a meteorologist, not a geologist. It does seem a bit petty – but perhaps that’s only to be expected from a community of egotists, each clawing for recognition of their individual genius (harsh but true).

Looking back, it’s easy to wonder how anybody could dismiss Wegener’s ideas so readily. However, we have more than the gift of hindsight at our disposal. Continental drift is now so crucial to the Earth sciences that we learn about it in school, making it impossible for us to imagine the world any other way. We can’t help but think inside a box – and we share this mental rigidity with the geologists of the early 20th century. They, too, were trapped thinking inside a box: only theirs was very different to ours. Theirs was built on land bridges. Also, let’s use the fancy name for these thinking boxes: scientific paradigms.

The land bridge paradigm

Other than scientific pride and ego, the main obstacle for continental drift was that there was already a perfectly reasonable explanation in place, thank you very much. Geologists knew about the matching fossils on either side of the Atlantic – of course – and understood perfectly well, thank you, that life couldn’t have evolved into identical states on isolated landmasses. As such, it was firmly believed that the continents had once been joined. How? Land bridges.

This might sound absurd to us now, from the comfort of our paradigm. However, the land bridge theory was built on the assumption that continents are stationary, which felt reasonable at the time, because the continents felt reasonably stationary. Even so, it was widely known that sea levels had risen and fallen in the past, as there were plenty of rocks on land that had clearly formed underwater. Geologists were therefore happy with the idea that land could rise and fall, slowly, on continental scales.

The explanation for all this land movement was the contracting Earth theory, which is barely remembered today. But at the time, geologists believed that the Earth was shrinking.

The Earth, shrinking?

In the early 20th century, it was widely believed that the Earth was cooling down and shrinking, with its crust generating wrinkles as a result. These wrinkles caused the land to rise and fall, which explained why seafloor sediments could be found on mountains, and why land bridges could have connected the continents before sinking out of sight.

The contracting Earth theory answered multiple problems very neatly. Better still, it was based on irrefutable physics: stuff shrinks when it cools, and the Earth must be cooling down, because it’s obviously really hot on the inside, space is obviously really cold, and there’s no way that the Earth could be generating heat, is there?

However, cracks were already developing in this theory when Wegener proposed his drifting continents. European geologists had noticed that the Alps required more uplift than planetary wrinkling could allow, and they soon realised that mountains could be built much better in collisions between sections of the crust – a concept which neatly aligned with Wegener’s drifting idea.

Unfortunately, the crinkling crust concept was around for long enough that many other theories were built on top of it. And, of course, if you’ve used these crinkly foundations to build your geological church, you don’t want some upstart meteorologist swanning in and tearing it all down. You’ve put your blood, sweat and delicate genius tears into this work – it couldn’t all be for nothing! As such, continental drift threatened the current understanding. If it was right, then many other things were wrong. And people don’t like being wrong.

Continents drift, paradigms shift

When Wegener first proposed his idea, evidence was rather thin on the ground. The concept of a solid crust on a flowing mantle was only just taking root, based on measurements of crustal rebound after glacial retreat. Through time, the pieces started to slot together: the discovery of subduction zones, seafloor spreading, rock magnetism, and finally, the ability to measure the movements of continents using GPS. It’s really quite upsetting that Wegener didn’t live to see his idea become widely accepted. Continental drift, and the understanding of plate tectonics that followed, changed the way geologists viewed the world.

However, it is still worth remembering the scientists who initially dismissed Wegener’s theory. Their rigid mindset, stubbornness, or pride are only obvious in hindsight, and we should try and learn from this. These scientists were operating quite happily within the confines of their paradigm, and couldn’t see the need for anything new. They thought the existing framework was sufficient, and – most importantly – they had little way of knowing otherwise.

All this makes me wonder… There must be problems today that we’re struggling to solve, simply because we’re working within the remits of a box constructed by earlier work. In fifty years time, will people look back and scoff at our ignorance? We can’t possibly know – and that’s rather daunting. We can’t conceive of anything outside our paradigm. In fact, the very concept of a paradigm is probably a result of thinking within a paradigm that will one day be overturned.

Whatever the case, it takes a special sort of person to see where radical change is needed. In the case of Alfred Wegener, it probably helped that he was an outsider to the geology community, because he wasn’t anchored down by existing ideas, and was free to form his own. And what an idea it was.

In summary…

I hope you enjoyed this longer-form post, and learnt something new along the way. Just a heads up that I may not be posting for a while. I have places to be and work to do, but I will try to be back by April!

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “Six-minute summary: Alfred Wegener”