Hello readers! Today’s blog post was triggered by a mundane observation that turned out to be interesting. Have you ever noticed that in a box of muesli, the largest pieces (e.g., Brazil nuts) tend to rise to the surface? I was reminded of this phenomenon yesterday, when I noticed that a bag of mixed herbs in my cupboard had stratified itself so that the smallest flakes of dried basil were at the bottom, while the large chilli flakes and seeds had migrated to the top.

This phenomenon is often called “the Brazil nut effect”, due to the way that Brazil nuts rise to the top of a bowl of mixed nuts. Wikipedia asserts that the scientific name is “granular convection” – but after a bit of digging, I’m not sure that convection is the whole story. As with any inexplicable everyday curiosity, plenty of scientists have had a go at explaining why large objects should rise when we might expect them to sink, but unfortunately, there is no way of shaking Google Scholar to bring the right answer to the top of the results. In fact, there are several competing theories to explain the Brazil nut effect, and nobody knows which one is “right” – or, indeed, if they are all “right” under different conditions.

Theory one: percolation

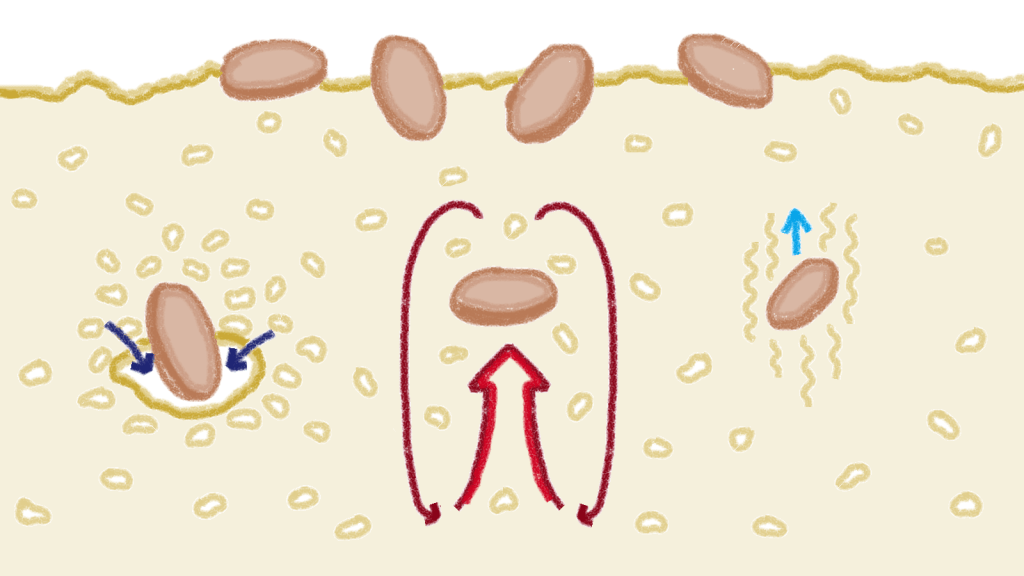

Percolation is where smaller particles can fall into the gaps left around bigger particles when the suspension is shaken. Once smaller particles have filled the gaps, they stop the big particle from settling downwards. Instead, any subsequent collisions with the big particle can only nudge it upwards, once again leaving a gap beneath it which is quickly filled by its smaller neighbours. In a nutshell, this means that, for the large particles, the only way is up.

However, there is more to this percolation theory than meets the eye. Scientists used CT scans on shaken mixtures of nuts, and found that the Brazil nuts only start to rise once they have been rotated into a vertical position. After a sufficient amount of jostling, a vertically oriented nut is in a better position for smaller nuts to fall down on either side, which allows it to ascend. However, the scientists also noted that nuts trapped at the bottom of the container never rise, even if they rotate into launch position. They propose that this is because smaller nuts cannot fall past them, meaning that the big nuts lack the support they need to attain their lofty goals.

Theory two: convection

This is slightly different to percolation, as we need to treat the particle mix as a fluid, rather than as a population of interacting solids. As a fluid, the particles can develop convection currents in their container, and these currents can carry large particles up to the surface. In a cylinder, the centre moves upwards while the edges move downwards, and large particles remain at the surface because they are too wide to fit into the downwelling regions. This is where things get really interesting. The scientists who discovered this effect created a conical container where the currents flowed downwards in the centre but upwards by the walls. In this case, the large particles were carried down to the bottom and became trapped there – a reverse Brazil nut effect!

Theory three: fluidisation

When you shake a bunch of particles hard enough, they can start to act as a fluid. You might have encountered this by jumping up and down on wet sand at the beach, or seen videos of liquefaction during earthquakes, where the shaking is strong enough to make the soil act like a liquid. Similarly, if we shake a box of muesli enough, the small grains making up the bulk of the mixture start acting like a fluid, and so the larger pieces of fruit and nuts start rising or sinking depending on their buoyancy. However, this behaviour is only likely to occur at high frequencies of shaking, so it can only explain the Brazil nut effect in extreme cases.

Some other weird effects that might play a role:

Fluids carrying particles are often dilatant, meaning that their volume expands when you try to force them to flow. This is because undisturbed grains settle into an interlocking heap, and the only way they can move is if they unlock from one another, which requires additional space between them. You see this on the beach when the sand under your foot ends up wet, while the sand around it appears to dry out. This is because putting weight on the sand forces it to move, increasing its volume. As a result, water flows in from the surrounding wet sand, making it look dry. Now imagine that the water was actually another suspension made of even finer particles. Having a range of particle sizes present will lead to some very strange behaviour, which may well cause the particles to filter and organise themselves.

The same dilatant behaviour of granular suspensions can also lead to them forming a heap of their own accord when their container is shaken. Particles become more concentrated and interlocked with increasing depth into a suspension, and so any slight variation from a flat surface leads to lateral concentration gradients. Areas beneath bumps are more compressed, while areas within dents are less so. Thanks to the dilatant behaviour, the least compressed areas are more mobile, as they can expand and unlock more easily. We end up with a net migration of particles away from the most mobile regions, leading to the particles concentrating towards bumps in the surface, essentially making mountains out of molehills. This is very strange behaviour indeed – and is similar to our Brazil nut effect in that it feels counterintuitive at first.

Another weird behaviour is the Bagnold effect, where particles in a granular suspension migrate away from steep velocity gradients. In a collision between two particles travelling at very different speeds, a greater amount of energy is transferred than if they had been travelling at the same speed. As such, particles in regions of steep velocity gradients suffer a greater lateral deviation from their original path, compared to regions with shallower velocity gradients. The result is a net migration of particles away from the edges of a flow, where velocity gradients are steeper, causing particles to be concentrated into its centre. Furthermore, larger particles migrate faster than smaller ones, leading to differentiation by size. Could this be yet another factor at play in the Brazil nut effect? Who knows.

In summary…

Who knew that a box of muesli could be so intriguing? I think it’s fascinating that something so mundane, which we have all encountered, is still not fully understood. It won’t necessarily benefit humanity to understand why Brazil nuts rise to the top of our muesli, but this process isn’t restricted to breakfast cereal (or mixed herbs). Many industrial processes might want to separate particles by shaking them, or indeed, to stop them separating by reducing the shaking they experience. Most industries will use a trial and error approach to get this right, so it could be argued that understanding the physics is a waste of time. However, this doesn’t make the problem any less enticing. Granular flows are wonderfully mysterious, and understanding the physics of my muesli would probably make it taste better.

Also…

I have a new book out! If you didn’t see the announcement yesterday, I have published a new book on Amazon. Sylvre is the second book in the Highmoor series, so if epic fantasy novels are up your street, why not take a look? (Link: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B0C7LVH17V)

References (in case you want to read more):

- Bagnold, R.A., 1954. Experiments on a gravity-free dispersion of large solid spheres in a Newtonian fluid under shear. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 225(1160), pp.49-63.

- Gajjar, P., Johnson, C.G., Carr, J., Chrispeels, K., Gray, J.M.N.T. and Withers, P.J., 2021. Size segregation of irregular granular materials captured by time-resolved 3D imaging. Scientific Reports, 11(1), p.8352.

- Knight, J.B., Jaeger, H.M. and Nagel, S.R., 1993. Vibration-induced size separation in granular media: The convection connection. Physical Review Letters, 70(24), p.3728.

- Rajchenbach, J., 1991. Dilatant process for convective motion in a sand heap. Europhysics Letters, 16(2), p.149.

- Shinbrot, T. and Muzzio, F.J., 1998. Reverse buoyancy in shaken granular beds. Physical Review Letters, 81(20), p.4365.

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.