Hello readers! Today’s six-minute summary is about Inge Lehmann, the Danish scientist who discovered that our planet has a solid inner core. I thought this summary would be somewhat topical following the recent media coverage of ‘giant blobs’ in the lower mantle, now proposed to be the remnants of an ancient collision with another planet (classic headline-grabbing science). The only reason we know anything about the interior of our planet is thanks to pioneering scientists like Inge Lehmann – and yet her name is barely known outside geological circles.

The Earth’s interior

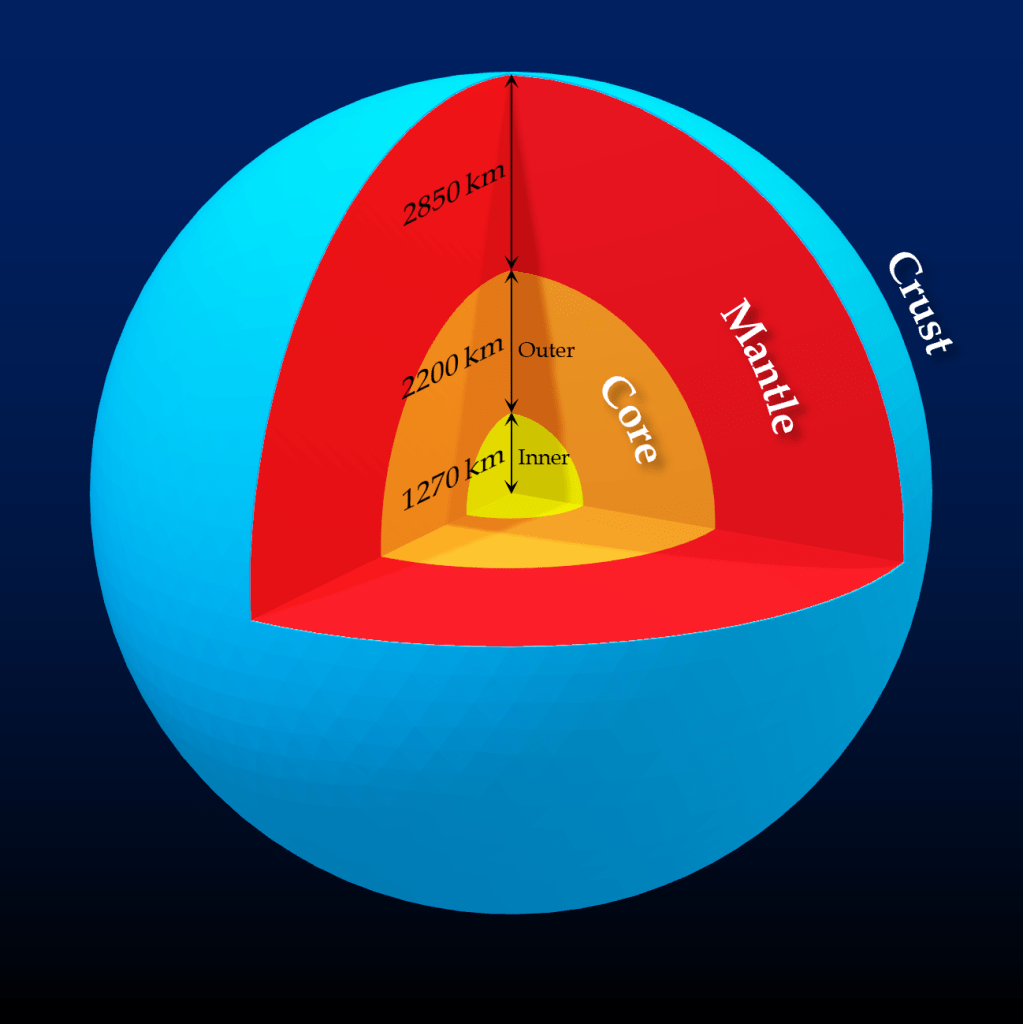

Everyone reading this probably has a rough idea of what lies within our planet. We’ve all seen colourful cross-sections of the Earth, with concentric spheres in various shades of orange. On the outside is the thin crust (home sweet home), then the mantle (the red-orange bit), then the outer core (the orange-yellow bit) and the inner core (the bright yellow bit). We might get a bit foggy when it comes to explaining the various thicknesses, temperatures, or physical states of the layers, but it is still incredible that most of us hold this model in our heads. It wasn’t so long ago that nobody had any idea what was down there. In fact, the structure of our planet was only discovered in the last century.

The Ancient Greeks saw Earth as a solid, rocky sphere, surrounded by spherical shells of water and air. They thought that volcanoes erupted due to powerful subterranean fires melting rocks, and this idea lasted centuries. The Christian model put the fires of hell at the Earth’s centre (of course), and only a few crazy individuals ever believed that the Earth was hollow (*cough* Edmond Halley *cough*). Newton proposed that Earth was predominantly molten based on its spherical shape, because a rotating, self-gravitating liquid would naturally form a sphere. People knew that there was something very hot lurking beneath our feet, but the temperatures and physical states of our planet’s interior left scientists stumped, even into the 18th century. The biggest obstacle was that there was no way of seeing what was going on.

The first modern ideas for the Earth’s interior were based on the rigidity of the planet. The ‘mostly liquid’ model was debunked in the 19th century by William Hopkins and his student, William Thompson (who would become Lord Kelvin). They suggested that the Earth must be predominantly solid due to the response of its rotation to the gravity of the Moon. However, it wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century that scientists devised a way to “see” inside the planet.

The birth of seismology

The 20th century was when Earth Science really took off. In under 50 years, we went from knowing very little about our planet’s interior, to knowing the depths and physical states of its major layers. This rapid advancement in our understanding was catalysed by the realisation that earthquakes could be used to image our planet’s interior. The field of seismology was born – and Inge Lehmann was one of the first seismologists.

The first person to use earthquakes to image the Earth’s interior was Richard Oldham. He identified three types of seismic wave, which travelled in different ways and at different speeds. At the turn of the 20th century, hundreds of seismometers were in use around the world, and by looking at the arrival times of different types of waves after an earthquake, Oldham reconstructed the paths that the waves had taken. He noticed that paths were distorted by an area of high density at the centre of our planet, and in 1906, he proposed the existence of the Earth’s core. In 1926, Harold Jeffreys established that this core was liquid. Then, in 1936, Inge Lehmann proposed that there was a solid core within the liquid core.

Who was Inge Lehmann?

Inge Lehmann was born in Copenhagen in 1888. She showed great intelligence from an early age, but her education was slightly unusual for the time, as she attended a school where boys and girls were taught the same subjects. This school had been set up by Hanna Adler, one of the first two women in Denmark to get a master’s degree in physics (she also happened to be the aunt of Niels Bohr). Many of the teachers at this school were female graduates who were unable to be employed at traditional high schools or universities. As such, Lehmann was taught maths and physics by some of the first women to hold degrees in those subjects, and she followed in their footsteps. She went on to study mathematics at the University of Copenhagen, and she graduated in 1910.

Having graduated, Lehmann was keen to study abroad. She enrolled at Newnham College, Cambridge – one of the two colleges for female students. Women had been allowed to sit the Mathematical Tripos (basically the hardest maths degree in the world) since 1881; however, women were barred from becoming official members of the university, meaning that they couldn’t access laboratories, libraries or one-to-one tutoring (equality was only achieved in 1948). As such, Lehmann was at a constant disadvantage to her male peers. She expressed her exasperation in letters to Niels Bohr, who had also come from Copenhagen to study at Cambridge. However, they struggled to meet in person, as this required Lehmann to organise a chaperone – yet another barrier to making connections and sharing ideas.

Lehmann faced many obstacles in her early academic career. Most sources claim that she suffered poor health due to her studies, and her father stopped her from returning to Cambridge, citing fears for her wellbeing and financial stability. He was a psychologist, and seemingly accepted the widely held belief at the time that women were too fragile to withstand academia. As such, Lehmann followed the path of many other female maths graduates, and worked at an insurance company until she was 29. At this point, she suddenly changed course. She got engaged, broke it off after one month, and shortly afterwards returned to the University of Copenhagen to get an MA in mathematics.

Director of the seismology department

After acquiring her master’s degree, Lehmann got a job as an assistant to a mathematics professor at the university. A law had been passed in 1921 that allowed the university to employ women in academic roles – although she was initially paid much less than her male counterparts. She took on other jobs around the university, including work for Niels Erik Nørlund, a mathematician involved in the creation of the Danish Geodetic Network (and who happened to be Niels Bohr’s brother in law, because seemingly everyone knew Niels Bohr). Professor Nørlund gave Lehmann the job of setting up new seismometer stations, and arranged four months of training for her, including a month learning from Beno Gutenburg in Germany. In 1928, Lehmann became the second person in Denmark to get an MSc in Geodesy, and soon afterwards she became the director of the seismology department at the geodetic network.

In her new role, Lehmann was responsible for running Denmark’s seismic stations. It was a permanent post with a salary, but most of the work was administrative, and she could only conduct research in her spare time. This was when she made the discovery of the inner core of our planet – and it is worth remembering that she did all this without computers. She kept all the physical seismogram cards in boxes, and read them all individually, interpreting global trends without any of the digital tools we use today.

Later life and legacy

Lehmann retired in 1953, but she continued to have an active role in the seismology community. Attitudes towards women were changing, and she started to receive recognition for all she had achieved. Still, I’m amazed that she isn’t more well known; indeed, none of the people who discovered the structure of our planet are household names. This is despite the fact that their discoveries have more impact on our day-to-day lives than any relativistic effects or giant black holes, which get a lot more media attention. The inner workings of our planet are part of a huge, interconnected system, and knowing the Earth’s structure helps us understand the processes that govern our lives on the surface. Lehmann’s discovery was monumental.

The University of Copenhagen awarded Lehmann an honorary doctorate in 1968, when she was 80. She died in 1993 at the age of 104, having lived through and participated in the most exciting, revolutionary decades in Earth Science. However, her early career provides a sobering reminder of the difficulties women faced in academia. Women were constantly overlooked, and this created a pressure for them to be better than their male counterparts, just to be noticed and taken seriously. Often, this resulted in exhaustion and breakdowns, which created a self-fulfilling prophecy and fuelled the belief that women couldn’t be academics . Although things have improved greatly in the last century, there is still a gender imbalance in academia, in terms of professorships, funding, and even the placements of names in lists of authors. It is worth remembering that such imbalances can skew our perceptions, either of our peers or of ourselves.

In summary…

Inge Lehmann was a trailblazing scientist. Her incredible discovery of the Earth’s inner core should be more widely known, and her findings are even more impressive in the context of her struggles to be a female academic in the early 20th century. We are still learning about what goes on inside our planet, and one day, we may be using the same methods to understand the interiors of other planets, too.

Further reading for those interested

An overview of Lehmann’s early academic career:

Jacobsen, L. L. (2022) Intellectually gifted but inherently fragile – society’s view of female scientists as experienced by seismologist Inge Lehmann up to 1930. History of Geo- and Space Sciences, 13, 83-92. https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-83-2022

An overview of the paper where she proposed the inner core (with nice diagrams):

Kölbl-Ebert, M. (2001) Inge Lehmann’s paper: “P’” (1936). Episodes Journal of International Geoscience, 24(4), 262-267. https://doi.org/10.18814/epiiugs/2001/v24i4/007

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Six-minute summary: Inge Lehmann”