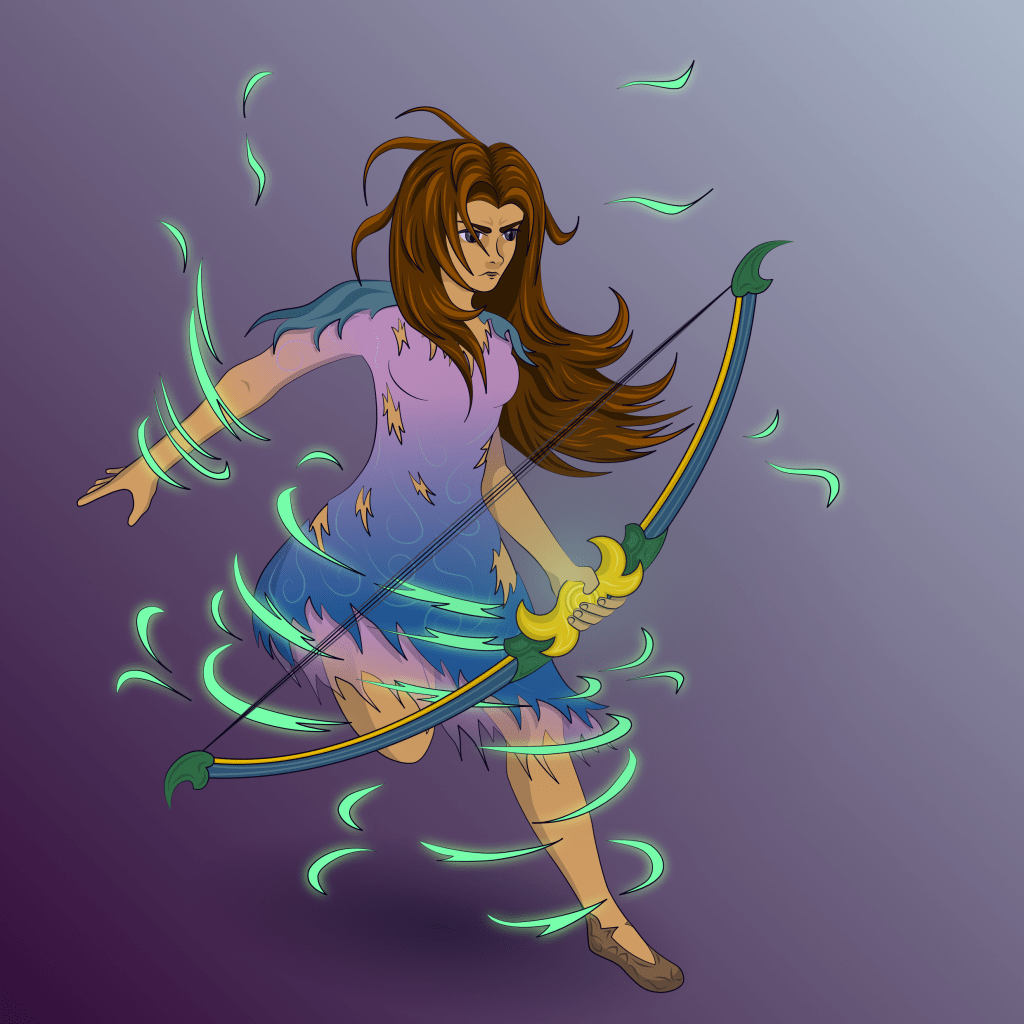

Hello readers! Today I’m adding a new character doodle to this blog’s “art collection”. This is a sketch of Trekja, one of the seven gods from my Highmoor fantasy series. She is the god of the atmosphere and the creator of dragons, and she is also the revered spirit of the people of Highmoor. I haven’t got much to say about the drawing itself, so I thought I would use this post to ponder the many ways that gods and deities are presented in fantasy, and the narrative conundrums that they create.

What do we mean by “gods” in fantasy?

There are many types of gods in fantasy, just as there are in the real world. They have different powers, interact with people in different ways, and have different physical forms. However, I think I can break the definition into three major groups:

Group A: An intangible presence. These are gods who are worshipped by people within the fantasy world, and who are believed to have created the universe or to control its workings. However, nobody within the fantasy world has any definitive proof of their existence. In fact, there may well be other cultures within this world that have adopted a different belief system, with a different set of gods.

Group B: The creators and protectors. These are gods who have a physical presence within the fabric of the fantasy universe. They created the world, or have since come into being to influence world events (with floods, droughts, plagues, etc.). They are often immortal, but they can have personalities and foibles, and they can take physical forms in order to interact with mortals, in a similar fashion to the Ancient Greek or Viking gods.

Group C: Powerful beings, despots and tricksters. These are physical beings with great power or influence who have convinced or coerced people to worship them. They did not create the world, and although they may attain powers that make them immortal or omniscient, they start life as another quirk of the universe, just like everybody else.

Obviously, these groups aren’t strictly definitive. There is plenty of overlap between Groups A and B, for example, because many authors don’t want to confirm whether gods truly exist within their fantasy world. It is often preferable to leave some sense of mystery, or to create parallels with agnosticism in our own world. Similarly, it can be hard to distinguish between Groups B and C if beings become so powerful or long-lived that nobody can imagine a world functioning without them.

The purpose of gods in fantasy novels

Fantasy media provides escapism to its audience by creating new worlds and new laws. However, these worlds always remain familiar enough for us to recognise and explore aspects of our own lives, but through a new lens. Throughout history, we have used stories to explore the themes of power, fate and belief, so it is no surprise that gods show up in fantasy settings in so many different forms. Authors include different types of godlike characters to explore different themes, sometimes from the perspective of mortals, and sometimes (increasingly?) from the perspective of gods.

Gods and worldbuilding

Group A gods exist simply to provide lore for the wider fantasy world. Religions are a key part of fantasy cultures, and religions usually need deities. Making up gods and creation myths for your world is just as important as deciding its fictional geography, and having named gods makes the alternative reality feel richer and deeper, even if their presence makes no difference to the plot. For example, Game of Thrones has plenty of religions, but the existence of their gods is never debated, because the plot revolves around human politics and conflict, rather than on theology.

Group B gods can be used in the same way. For example, Tolkien states that Middle Earth was created by a powerful being, but none of the people in his stories really worship this god or pray for his help. The god might exist, but he has no bearing on the story. Although Tolkien was a religious man, there is a decided lack of fictional religion in Lord of the Rings; characters have faith in themselves and their friends, rather than in higher beings, and they accept that they must take matters into their own hands. The god only exists to expand the lore (as if it needed expanding).

Gods as characters

Group B gods can also be central to the story, with their personalities and powers forming a critical part of the plot. An obvious example is American Gods by Neil Gaiman, or the Kaos series that has just appeared on Netflix. Group C gods often play a similar role, appearing as both protagonists and antagonists. Examples range from non-magical tricksters like the Wizard of Oz, to genuinely powerful characters like Paul Atreides in Dune. Plenty of fantasy stories have gods as main characters, and even though they share similar themes, it isn’t quite a genre in itself.

To me, the one of the strangest cases of gods in fantasy is in the Narnia series. These books are often deemed to be allegorical, teaching kids bible stories by stealth, but the later storylines get decidedly weird. C. S. Lewis wrote Aslan to be the reincarnation of Jesus in a world of talking animals (a perfectly normal and unproblematic thing to do), and he then uses him to explore the meaning of Christianity, often by casting other religions in a very unflattering light. But in a strange twist for a children’s book series, Lewis also decided to explore the apocalypse and judgement day. Major spoilers here, but literally all the children die. It’s wild.

Other authors include gods for entirely satirical purposes, with Terry Pratchett’s Small Gods being a prime example. The Discworld books have hundreds of godlike characters, because its unique ecosystem means that belief itself gives rise to their existence. It’s very silly, and exists in its own quirky fantasy sub-genre, but it certainly gets you thinking.

The problem with godlike powers

There are all sorts of gods lurking in fantasy media, and people have some strong opinions about their inclusion – especially when it comes to high fantasy. Group A gods face the least resistance, because they add flavour to the world without prompting philosophical arguments. However, the gods in Groups B and C bring with them all manner of problems, especially when readers deem characters to be “overpowered”.

In fantasy media, it is vital to balance the power of protagonists and antagonists in order for their conflict to remain engaging. If a character becomes too powerful, winning every fight, it can be difficult to create tension or jeopardy. Bringing down a god character usually involves some kind of trick, and if this is handled badly (for example, if the solution is pulled out of thin air at the last second), their downfall can come off as implausible or downright stupid. It’s a big problem for the superhero genre, too. Fights have to carry weight, or the audience tunes out.

Of course, I’m not saying that god or godlike characters can’t be employed effectively. Meaningful storylines can be created by exploring how the character’s powers influence their relationship with others, perhaps by learning to help them, or by unintentionally alienating them (see Mob Psycho 100 for a fantastic handling of this). There are plenty of engaging stories out there regarding god complexes – although with the superhero genre having become so mainstream, I do wonder if this theme is starting to get a little bit tired.

Common reader quibbles

I think the most common problem with gods in fantasy is a lack of remits. If you don’t explain to readers exactly what a god can do, then they will be left to fill in the blanks with their own preconceptions. Yes, there is always room for a bit of mystery, or for indescribable powers beyond our mortal comprehension, but these should be presented in a consistent manner. The same is true of magic systems (but that deserves a blog post of its own).

Another problem that seems to irritate some readers is the concept of gods being fallible. I think this probably stems from preconceptions of an omniscient, omnipotent and omnipresent god, and it may be somewhat jarring for these readers to consider a god with human traits such as arrogance or complacency. If you can’t accept that a god would make mistakes, then the tricks and plots that authors concoct to bring them down won’t feel satisfactory. This isn’t the fault of the author or the reader – they just have fundamentally different ideas of what a god should be.

So, what kind of god is Trekja?

Trekja falls into Group B. She and six other gods created the world and its people, and they lived alongside their creations for hundreds of years. However, the gods eventually lost their physical forms and became spirits, barely able to exert the slightest influence over the world they once ruled. The Highmoor series is set nearly two thousand years after the gods faded. Nobody prays to Trekja anymore, because her powers are insignificant.

The echoes of Trekja’s strength reverberate through the aether – the intangible plane through which dragons communicate telepathically. Her wisdom is evidenced in the ancient runes she left behind, instructing the dragons on how to fashion rhaffgled blades. She also left behind her sacred bow, which can reportedly fire shockwaves that send witches’ brooms tumbling from the sky. However, nobody has seen this bow in centuries. Does it still exist, and can it still be used? Probably, or else I wouldn’t have mentioned it.

In summary…

I hope you enjoyed this brief ramble regarding the nature of fantasy gods. I’ve been pondering this topic a fair bit lately (which might give you some idea of where the final Highmoor book is heading). I’ll upload more character doodles when I can, and provide progress updates on the fourth book as it develops. Happy reading, and have a lovely week!

(Also, for those that missed the news: the third book, Synwyr, is available now!)

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.