Hello readers! Have you ever wondered what a star rating really means? Our online purchasing choices are often guided by tiny rows of stars, but their meaning isn’t as clear as their simplicity would suggest.

Ratings are everywhere, whether they are individual scores given by respected critics, or mean values harvested from thousands of users and bots. Most are presented as marks out of five (or sometimes ten or one hundred), but there are also strange alternatives such as the “Tomatometer” on Rotten Tomatoes. These numerical values impact our decisions in various settings, from buying books, games, or furniture, to deciding which film to watch, or where to eat, or who we should hire to sort out the rising damp on the wall behind the sofa.

Today I’m going to explore the hidden rules that we use to provide and interpret numerical ratings of products and media. I’ll break down some common approaches for calculating ratings, discuss some simple statistics, and explore the issues that arise when various rating methods are combined into a single metric.

Many different methods

Imagine that you’ve just read a book. You have flicked over the final page, and your Kindle has thrown you a pop-up box asking for a star rating. Amazon doesn’t provide you any guidance on how the rating system works, so your star score must be based purely on instinct. Maybe you have a method – but it will probably be different to other readers. As I see it, there are four main approaches:

Method 1: Keep things purely objective. Given that the lowest score you can give is one star out of five, three stars out of five is the centre of the scale. You will therefore award three stars if your experience with the book was neutral – if it contained an equal number of good and bad aspects. Anything below three stars implies more bad than good, and anything above three stars implies more good than bad. Simple. A one-star book is irredeemable. A five-star book is flawless.

Method 2: Score based on context. You have read a lot of books, and you know the amount of enjoyment that the average book provides. Your experience provides the context for you to rate other books. So, you consider three stars, the central score, to be the average. Anything above three stars is better than average, and anything below three stars is worse than average.

Method 3: Negative marking scheme. You start reading the book with an open mind. Before you open the cover, it has five stars. Then, as you read, certain aspects might start to bother you, so you deduct points from your score. If the book still has five stars by the time you finish reading, then it was flawless.

Method 4: Gut instinct. There is no system involved here. Having finished the book, you just have a feeling for how many stars it deserves. Maybe, in the back of your mind, you had some sense of evaluating the good aspects versus the bad – and perhaps you deducted or granted marks subconsciously, even if you didn’t define your starting point. Put simply, a five star book made you happy, and a one star book left you disappointed.

Rules and reliability

By not providing any guidelines for its rating system, Amazon leaves everything in the hands of the reviewer. This undermines the ratings, as everyone will be working from a different baseline. Obviously, opinions on products will vary – but it is hard to establish true differences in opinion when everyone is using their own marking system. This problem is then compounded when ratings are combined into an average score.

As an example, imagine that we have four people with the same opinion of a book. Person A uses Method 1 and gives a score of 4/5, because the book definitely did more good than it did bad, and was an enjoyable read overall. Person B uses Method 2, and gives a score of 3/5, because although the book was enjoyable, it was no more enjoyable than average.

Person C uses Method 3 and also gives the book 3/5 – because although it was fun, it had a few really annoying sections. Person D uses Method 4 and gives the book 5/5, because even though the story wasn’t groundbreaking or original, and was by no means perfect, it was exactly what they needed to fill five hours on a rainy weekend.

If we take an average of these scores, what do we learn? The book now has a score of 3.75 stars on Amazon. Is it worth reading? Perhaps this score is high enough for you to take a look at the written reviews, where you’ll get a better idea of what people thought about it. But maybe 3.75 isn’t high enough to draw you in. Maybe you will just keep scrolling.

Which method are you?

I’m genuinely interested to know the methods that people use to provide ratings. I have no idea whether most people are Method 1 or Method 4 – or if they use an entirely different system (e.g., an automatic five stars on anything involving Taylor Swift). Obviously, opinions are subjective and tastes vary, but unless we’re all using the same system, it can be difficult to ascertain how and why opinions are diverging.

Case study: The three whisks

Why whisks, you ask? I was looking for something incredibly mundane with a very simple purpose, where opinions should be more objective. I went looking for the cheapest whisk available, and found a set of three for less than £4. Based on this price, these whisks should be the worst on the market (probably collapsing under the strain of a single egg), and yet, as is often the case on Amazon, the product has 4/5 stars.

What does this tell me? Are these whisks better than your average whisk? Surely not. Are they better than I might expect from the price? Perhaps – but I am a pessimist and the bar is set extremely low. Maybe the score implies that these are good whisks aside from a few small drawbacks? The only way to find out is to compare the ratings to the written reviews, so let’s take a look.

Ah yes. Photo reviews – my favourite. Lots of broken whisks, which is exactly what I expected… Although we should anticipate some bias here, because who would share a photo of an unbroken whisk?

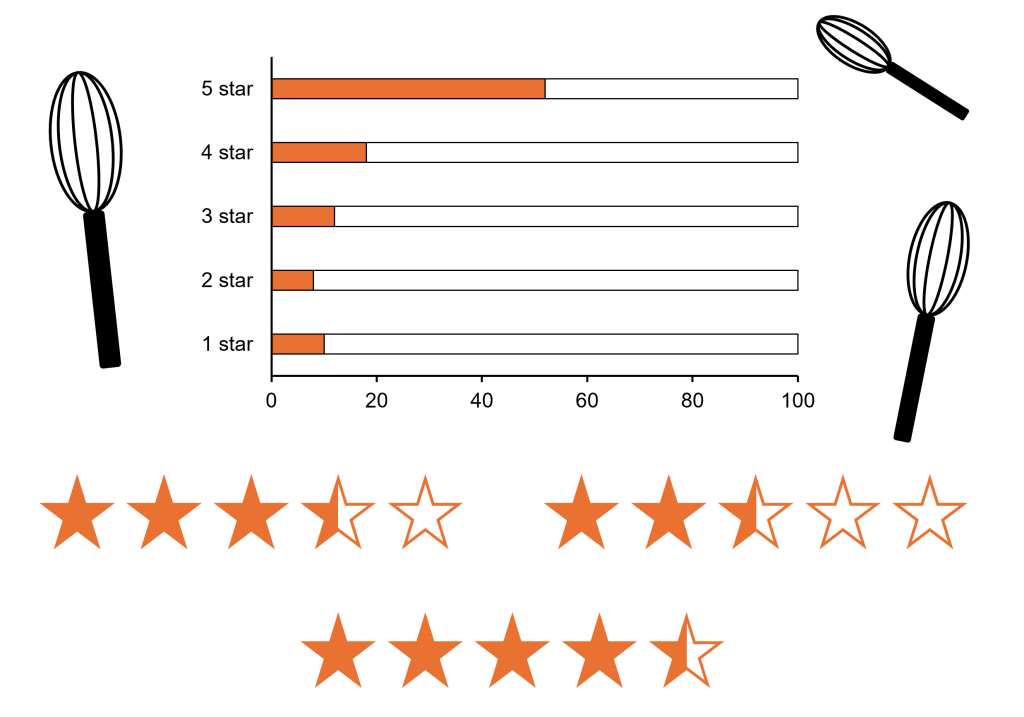

The rating breakdown is interesting. 52% of customers gave these whisks 5/5, and 18% gave them 4/5. At first glance, the ratings suggest that these are damn good whisks… I mean, a five-star whisk must be the whisk of your dreams, right? Do you not dream of whisks?

Amazon tells us that the average rating is 4/5, and a quick look at the numbers reveals that this is a mean average – in other words, this is what we get if we add up all the ratings, and divide by the number of ratings. However, the most common rating (i.e., the mode) is 5/5. And if we look at all the ratings in an ordered list, the value in the centre of this list provides us with the median, which is also 5/5. The mode and the median might actually be more useful to us, because they tell us the rating that the majority of people gave to this product. This just shows that the distribution of ratings is more important than the mean average.

So, most people gave these whisks 5/5. But how did they earn these ratings? Were these whisks so powerful that the very sight of them caused eggs to beat themselves?

A number of reviews justify 5/5 as being “good value for money” – which, given that these whisks were abysmally cheap, means very little. If I pay £4 for three whisks, I expect them to fall apart during their first use. If my expectations are met, do I award them five stars? The majority of customers seem to think so.

Then there are the chaotic reviews:

- 4/5: “Misleading information! Packet claims they are dishwasher safe but they fall apart in the dishwasher!”

- 5/5: “Just the job. Do not put in the dishwasher as they will rust.”

- 2/5: “A bit flimsy. If you whisk too hard the handle comes off.”

- 2/5: “Not as listed – pack says 8, 10, 12 inch whisks, and they are 8, 9 and 10.”

- 1/5: “Not as advertised! I needed the biggest whisk available and now my time has been wasted because of incompetence at Amazon!”

Here we see a very weak correlation between customer satisfaction and ratings. Clearly, some people are perfectly happy with a cheap whisk that falls apart or rusts in the dishwasher, whereas others deem a critical loss of structural integrity as nothing more than a bit of flimsiness. I am also left wondering why one reviewer needed such a big whisk. Did they have a really big egg?

A consistent lack of consistency

Our discussion so far might suggest that customer ratings are not fit for purpose. Given that people have differing opinions and use differing rating systems, why do we bother using ratings at all? Despite being entirely unsystematic, it seems that ratings still serve a purpose.

The usefulness of ratings comes down to the sheer number provided. Most of us have bought enough products and read enough reviews that we can correlate scores with outcomes, even if we do this subconsciously. We can’t know the reasoning behind any individual rating, but once 5000 people have offered up their verdicts, patterns start to emerge. This is a big numbers game. A balance of probability.

We know that there are people who give 5/5 when the product meets their basic expectations. We know that there are people who would give 1/5 to a product because they failed to read its description and were disappointed when it didn’t meet their misplaced expectations. We also know that there are crazy people out there who would give 5/5 to a chocolate teapot, even if the product had been listed as a flat-pack aluminium shelving unit. But once there are enough people offering their opinions, the discrepancies are ironed out.

In fact, we can still glean information from ratings even if half of them are provided by bots. Our pattern recognition can account for this, because we just establish a new baseline. We know that cheap tat on Amazon commonly scores a 4/5, so this becomes the new average. The same is true for Google reviews of films, which always have much higher scores than IMDB or Metacritic (apparently 82% of Google users enjoyed Prometheus). In short, the rating system is only useful in the context of the platform.

What about critics’ ratings?

It is harder to interpret the ratings of individual critics. Without the help of big numbers and probability, the rating depends more heavily on the opinion of the reviewer, and the method they used to generate the score. Everyone can agree that five is good and one is bad, but interpreting the central scores is almost impossible. Is a 3/5 book worth reading?

If you have followed a reviewer for some time, you’ll have a better idea of how they do things. Perhaps they are a Method 1 person, and a 3/5 means that a book was a neutral experience for them. Or perhaps they lean more towards Method 2, and a 3/5 means that the book was average compared to all other books – in which case, it should be sufficiently entertaining.

We also need to remember that reviewers tune their ratings to the tastes of their audience. Star scores in the Daily Mail will often differ from those in the Guardian, because they rate media according to a different set of values. They know that their audience may value some attributes more highly than others (for example, feel-good factor versus writing quality) and will provide ratings that reflect this. These opinions are easily expressed in the written review, but when it comes to the rating, the methodology and the motivations are hidden.

I would be interested to know how critics decide on their scores – whether they take a systematic approach, or go on gut instinct alone. How do they decide between four and five stars, when it could make or break a creator’s career?

Finally, a rant about the Tomatometer:

Rotten Tomatoes is probably the most popular platform summarising critics’ reviews of films and TV shows. The critics can either give the film a fresh tomato or a rotten tomato, depending on whether they liked or disliked it. The score for a film is then the percentage of critics who gave fresh tomatoes.

This is a very different way of rating a piece of media, and it has its own unique problems. A film with an 80% rating on Rotten Tomatoes does not make it a film worthy of 4/5 stars. Just because 80% of critics liked a film doesn’t mean to say that they loved the film. In fact, we can imagine a scenario where 100% of critics award a film 3.1 stars. All of them would admit that the film was good overall, or slightly better than average, but it was by no means a standout masterpiece. However, this film would get 100% on the Tomatometer.

Rotten Tomatoes inflates the scores of films that are widely regarded as being slightly better than average, and deflates the scores of films that are widely regarded as being slightly worse than average. Generic, crowd-pleasing films will generally go down well, and may score more highly than slow-paced or thought-provoking films that push boundaries. Perhaps the Tomatometer can provide a very quick insight into whether you’ll enjoy a film, but in many ways, it tells you even less than the distribution of star reviews on Amazon.

In summary…

The meaning of a rating is known only to the person who gave it, unless they are kind enough to provide an accompanying written review. That being said, ratings are still a useful indicator of quality once enough of them pile up. Although people don’t tend to buy things based on star ratings alone, average customer ratings play a significant role in our decision making process. For this reason, I always encourage people to leave star ratings – but I would never try to dictate a method for doing this. If everyone suddenly switched to following a strict set of guidelines, we would have to retrain our pattern recognition, and all previous ratings would become more meaningless than they already are.

Happy reading, and have a lovely week!

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “Reading into ratings – what do they mean?”