Hello readers! Last week I was on holiday on Lanzarote, a volcanic island off the northwest coast of Africa. Here in the UK, the island has a reputation for being a package-holiday hotspot, and it’s a popular destination for Brits seeking cheap alcohol and horrific sunburn. Millions of people travel to the island each year with the sole intention of remaining cooped up in concrete resorts – but beyond the sprawling tourist complexes, Lanzarote is crammed with natural wonders and oddities that demand to be explored. The island is the product of millions of years of volcanic activity, and is littered with cones and solidified lava from historic eruptions.

This week I’ll discuss what I got up to in the northern part of the island, which is home to several kilometres of towering cliffs, a handful of sheltered, white sand beaches, and one of the largest lava tubes on Earth. Next week I’ll be back to talk about the southern part of the island, including the lava fields and coastline of the Timanfaya National Park.

Introducing Lanzarote

Lanzarote is one of the Canary Islands, which comprise an archipelago off the northwest coast of Africa. The islands are an autonomous community of Spain, and the locals speak Spanish – although the region receives so many tourists that you’ll often find descriptions and menus written in English too. Lanzarote has a population of around 160,000, but three million tourists visit the island each year. It isn’t a big island; roughly speaking, it’s 60 km long and 20 km wide, making it slightly smaller than the Isle of Mull.

However, it is still relatively easy to find quiet areas of Lanzarote. I visited in late October, and even the tourist hotspots didn’t feel too busy. Many tourists remain solely within their hotel complexes, which are concentrated in the towns of Arrecife, Playa Blanca, and Costa Teguise. It was difficult to find areas that were entirely isolated, but most places weren’t crowded – especially not in the north.

First sight of the island

Before setting off to Lanzarote, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I’d been to Tenerife a couple of times before, on geological excursions, so I had a vague idea of the weather and the culture, and had just enough Spanish to survive a trip to the supermercado. However, when Lanzarote crept into sight beyond the aeroplane window, I realised that the island was much flatter and more arid than its westerly neighbours. From above, it appeared as a glowing amalgamation of beige and black, protruding from the ocean, with not a hint of greenery on its hills. Its low elevation leads to very little rain – unlike the more mountainous Canary Islands, which host verdant, vegetated areas on their windward sides. The highest point on Lanzarote is only 672 m above sea level, and the result is an island that is dusty and barren.

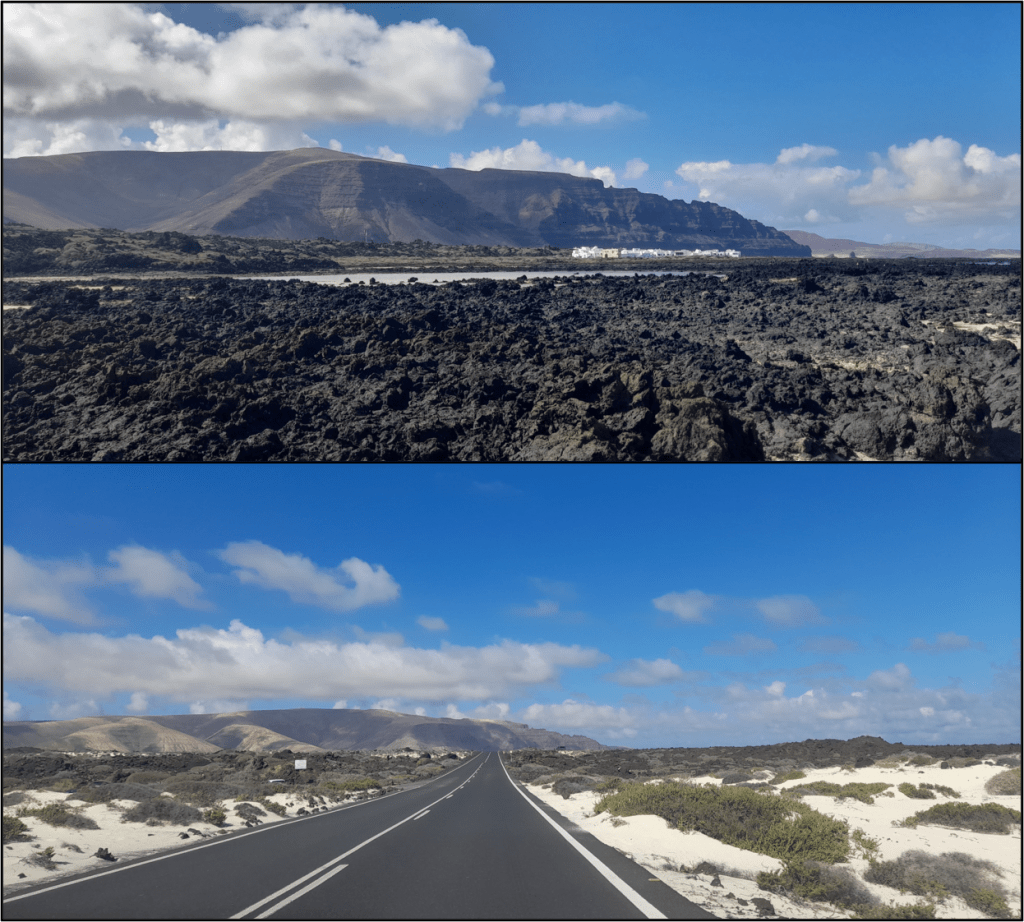

There are no lakes or rivers to be found on Lanzarote. Virtually all of the mains water on the island comes from desalination plants, and actual biological plants are few and far between. Towns and villages have palm trees and flowering bushes by the roadsides, but these are irrigated; outside the settled areas, the only flora you’ll see are succulent plants or cacti. Beyond the well-tamed gardens and golf-courses, Lanzarote is bereft of greenery. The landscape is rocky and desolate, with the history of its volcanic formation laid bare.

Costa Teguise

We based ourselves in Costa Teguise, a town built in the 1980s to house booming numbers of tourists. Its skyline is dominated by a handful of very large hotels, and dozens of smaller complexes are crammed into its grid-like layout. The town is only fifteen minutes from the airport in Arrecife, and package-holiday buses form the clots in its arterial roads.

If you are looking for tradition or culture, then Costa Teguise is not the place to be. Most of the people staying here are British, and all the local amenities have warped to suit British needs. There are several bars claiming to be pubs, showing football on big screens and serving meals in baskets. There are local shops stuffed to the gills with cheap booze, selling Cadbury chocolate alongside fridge magnets of parrots or naked women. There are an astonishing number of Indian and Chinese restaurants, most of which display faded photos of their food in their front windows, in case you had forgotten what korma and chips looked like. The town is the very embodiment of the “Brits abroad” stereotype, and it managed to fall short of my expectations while being exactly what I expected.

Overall, we spent very little time in Costa Teguise, using it only as our base camp. Each day we set off to explore another corner of the island, then came back when daylight faded, only to see the giant hotels lit up like science-fiction horrors on the horizon. Still, although I paint a grim picture of the place, it wasn’t without its charms. We had some great tapas and some fantastic ice cream, and everyone around us seemed to be having a great time. Who am I to judge if their holiday highlight was chicken in a basket followed by bingo? Not everyone loves rocks as much as me.

Heading north

On our first day, we headed to the very tip of the island, towards the town of Órzola. The mountains here are the highest on Lanzarote, and they have steep cliffs that plunge into the sea. A series of volcanic cones line the top of the ridge, the most prominent of which is La Corona, which formed 21,600 years ago. The main road passes through the solidified lava from this eruption, which extends down from the mountains as a black, jagged blanket, spreading towards the coast. Near the sea, the lava has eroded to produce sheltered bays filled with white sand. The best of these is Caletón Blanco, which forms a shallow lagoon 200 m long. If you have a snorkel, it’s a great place to go and swim with some fishes. Or, if you’re as fish-phobic as I am, you can swim around without looking down, refusing to acknowledge that the fishes exist. It’s a beautiful place either way.

Mirador del Río

Having been for a swim, we headed up into the hills. As this was the first day of our holiday, we didn’t have a firm grasp on the geography of the island. It was therefore something of a surprise when we followed the winding road up to the top of the ridge, past the volcanic cones, and discovered that the mountains suddenly drop away. The northwest coast of Lanzarote has towering cliffs, standing 500 metres tall before the sea.

The winding road leads to the Mirador del Río, which is a viewpoint built inside the cliffs, looking out across the sea towards the Chinijo Archipelago. It’s an astonishing place, housing a café and a gift shop behind huge windows, and boasting a series of balconies and platforms outside. I can’t imagine how they built it, and it’s hard to understand how the place remains standing. You feel as if a particularly large earthquake (or indeed, a particularly large tourist bus) could send it toppling down to the sea.

The Mirador del Río was designed by César Manrique, a Lanzarote artist born in Arrecife, whose works can be found across the island. He helped make Lanzarote a tourist destination, and built structures such as the Mirador del Río so that the tourists could appreciate the natural wonders of the island. His designs are inspired by the natural shapes found on Lanzarote, especially the volcanic processes. The walls here are decorated with slabs of ropey pahoehoe lava, and two huge sculptures hanging from the ceiling mimic the arcs traced by molten material thrown from a volcano.

The Mirador del Río poses a challenge even for people who claim to have a head for heights. The view is incredible, and worth the wobbly knees, but even from behind the glass you can feel the weight of the drop. Outside, the balustrades are a little too low for my liking, being just at waist height, and I was astounded by the number of people leaning their entire weight against them, turning their back on the drop in order to get the perfect selfie. They clearly trusted their balance more than I trust mine. Several phones were held above the void that day, and I’d be amazed if there isn’t a sparkly heap of microchips 500 metres below.

Jardín de Cactus

Later in our holiday, we returned to the north of the island to visit the Jardín de Cactus (the Cactus Garden). This is another project from César Manrique, and it contains sculptures, rocks, and a collection of cacti from around the world. There are about 4500 specimens in total, with 500 different species. Some of the plants are huge, creating enough shade to rival an oak tree, while others climb up walls like barbed ivy, or spread over the ground like puddles of needles. You really have to watch your footing around this place – although that’s just a general rule when walking around Lanzarote. Either the rocks are spiky, or the plants are spiky. Usually both.

Although César Manrique may be best known for the Mirador del Río and Jardín de Cactus (and possibly the airport, which is named after him), his influence extends beyond his artistic works. While he was alive, he encouraged tourism on Lanzarote, but campaigned for it to be sustainable. Although he passed away in 1992, the foundation that he set up still campaigns for environmental sustainability, and protests against the construction of high-rise tourist resorts, which threaten the island’s status as a UNESCO biosphere (more on that next week). The way that the island looks today is largely due to Manrique’s vision.

Cueva de Los Verdes

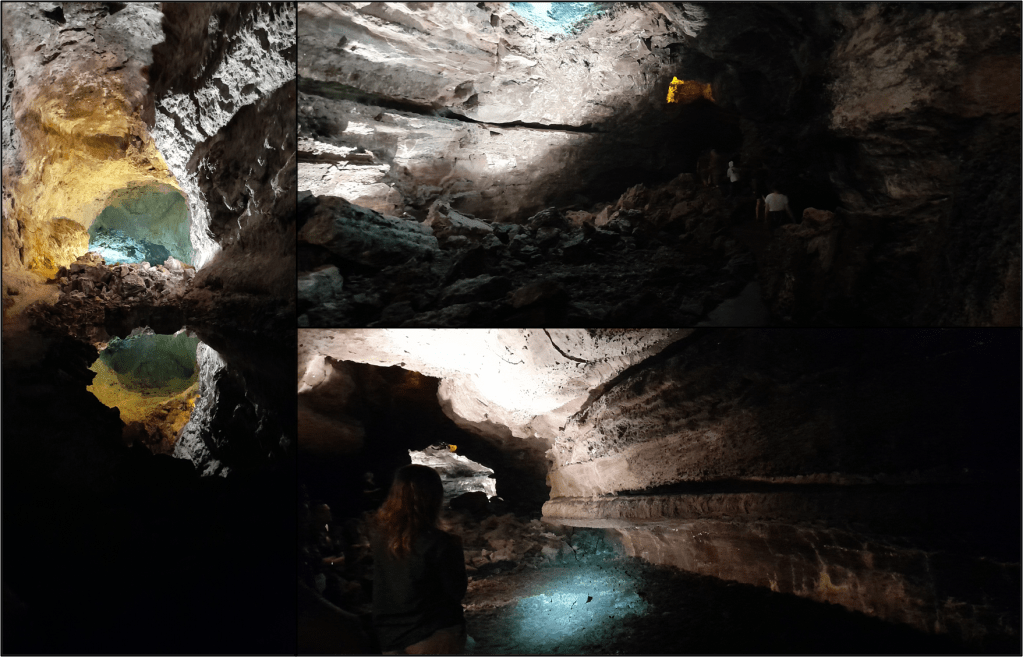

Just up the road from the Cactus Garden is the Cueva de Los Verdes. This literally translates as “Cave of the Greens”, and although this name initially summoned mental images of a subterranean broccoli farm, it turned out that these caves were named after the Verdes family (the Greens) who once lived here. The caves exist within a long, hollow tube structure that snakes through the solidified lava of the La Corona eruption – the one which created the huge cone at the top of the hill 21,600 years ago. Guided tours access the tube through a partial cave-in, right in the centre of the jagged lava field, and if it weren’t for the frequent signposting and conspicuous tourist buses, you would never guess that these caves were here.

The Cueva de Los Verdes is part of one of the biggest lava tubes on Earth. The tube system comprises a long, hollow conduit up to 28 metres in diameter, which meanders through the solidified lava flow for 6.1 km, all the way from the volcanic cone at the top of the hill, down to the sea. The tube then continues for another 1.6 km underwater, where the conduit is fully submerged.

The guided tours visit parts of the tube which are up to 15 metres wide and tens of metres high. Its full height is divided into layers, with one or two tubes resting on top of each other, connected by narrow holes and cave-ins. A concrete path winds along the lower tube, then climbs up to the higher tube before making its way back, skirting some surprisingly perilous drops. The biggest surprise, however, was the grand piano sequestered deep within the cave system, set up for subterranean concerts.

What is a lava tube?

Lava tubes form within big lava flows, like those on Hawaii or Iceland. The lava from these volcanoes has a basaltic composition, giving it a relatively low viscosity (a runny consistency) which lets it flow faster. Lava cools quickly in contact with the air, but it remains hot and molten beneath its solid outer skin. This allows conduits of hot, flowing lava to develop beneath the cold, stagnant surface. Lava within a fully developed tube is insulated from the air, and a long lava tube like the one from La Corona can transmit lava from the erupting vent to the front of the advancing flow without it losing much heat at all. They are the arteries of long-lasting lava flows, and when the eruption ends, cutting off the lava supply, the molten content of these arteries drains away, leaving a hollow conduit behind.

When you stand in Cueva de Los Verdes, you are standing in a conduit that was once filled with flowing lava. The lava was so hot, and the eruption so long-lived, that the base of the tube started to melt downwards into the rocks beneath, making the tube even deeper. The horizontal bands along the walls mark the height of the lava as it flowed through the tube. The lava level dropped over time, but when it stayed at a certain level for long enough, it would start to crust over, leaving shelves of solid material attached to the walls. At some point, the lava within the tube crusted over entirely, and when it eventually drained away, this solid crust remained, splitting the tube into two levels.

The lava tube is also home to thousands of jagged, pointed structures that protrude down from its ceiling and trail over its walls. These dangling structures look a bit like stalactites, but on an island as dry as Lanzarote, stalactite formation is impossible. Instead, these thousands of drip-like formations are solid rock, and they formed while the lava was flowing. The lava was around 1200 °C, and this was enough to start melting the tube roof, causing it to drip downwards like candlewax.

Next week: more volcanoes!

This wraps up part one of my Lanzarote trip. Next week I’ll talk about my adventures in the south of the island, in the Timanfaya National Park, which is home to Lanzarote’s youngest volcanic features. There will be bigger volcanic cones, bigger lava flows, lots of smaller tubes, and a whole host of other volcanic quirks that left me fascinated and astounded in equal measure.

Some final notes…

The Mirador del Río, Jardín de Cactus, and Cueva de Los Verdes are all run by CACT (the centre for art, culture and tourism on Lanzarote). They manage a few of César Manrique’s projects, as well as other museums and information centres around the island. If you were thinking of visiting Lanzarote and wanted more info, their website is well worth a look:

If you want a detailed description of the La Corona lava tube, with some excellent diagrams and photos, I recommend this paper, which (I think) is fully open access:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2022JB024056

Finally, long-time readers will know that this isn’t the first mention of lava tubes on this blog! I visited one last year on my trip to Iceland, and I’m afraid to say that Cueva de Los Verdes was rather more impressive than the Lava Cave. And much cheaper. Sorry Iceland!

Happy reading, and have a lovely week!

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

3 thoughts on “Clayton goes to Lanzarote (Part One – The North)”