Hello readers! I recently went on holiday to Lanzarote, and I have split my adventures and musings into two posts (see part one here). This week concerns the southern half of the island, which is home to its youngest volcanic features, located in and around the Timanfaya National Park.

This week’s post will cover my trip to the southern coastline, with its sandy beaches and hidden rockpools, and the volcanic inland, with its dozens of volcanic cones standing like islands in a sea of solidified lava. Along the way, I’ll discuss how these features formed, how people interacted with them in the past and present, and the region’s protected status.

Playa Blanca and Papagayo

The southern coast of Lanzarote is home to Playa Blanca – one of the newest and largest tourist towns on the island. We steered clear of the beaches in the town itself, anticipating them to be busy, but we made an effort to reach Papagayo, the most southerly point on Lanzarote. The only way to get there is by driving along a rocky track for over four kilometres, but that didn’t deter us – and nor did it deter the hundreds of other tourists. I have never seen so many Fiat 500 hire-cars veering so close to annihilation.

From Punta de Papagayo, you can look out across the sea to the neighbouring island of Fuerteventura, just over 10 km away. The Papagayo beach is in a secluded cove beneath the cliffs, and is stunningly beautiful but stupidly busy. The clean white sand and clear turquoise waters make it a wonderful spot for swimming and snorkelling, but you’ll always be in earshot of at least four families’ conversations. Papagayo is certainly worth a visit, but it’s good to know what to expect before you risk life and limb and several hundred euros of hire-car damage to get there.

The rockpools of Los Charcones

If you’re looking for a lonelier stretch of coastline, the region north of Playa Blanca is a better bet. This is where you’ll find the rockpools of Los Charcones, trapped on a narrow shelf of solidified lava between the rugged cliffs and roaring sea. There are no sheltered bays here, and no soft sand to absorb the ocean’s energy. Even on a relatively calm day, the waves are enormous – but if you time your visit with the tides, you’ll find rockpools that are cut off from the swell and the spray. A little bit of common sense goes a long way here; we spent quite a while understanding the layout of the pools, learning where strong currents formed, and where the biggest waves could overtop the natural barrier. It’s definitely worth a visit if you fancy something more adventurous.

Getting to the rockpools of Los Charcones is a challenge in itself. This corner of the island is a barren wilderness, and the few tracks that wind their way to the cliffs are in no way suitable for economy hire cars. We parked just off the main road north of Playa Blanca, then walked almost 2 km in a screaming, dusty wind across the desert. The rock pools were a very welcome sight after our trek – and luckily, scrambling down the cliffs was easier than it looked. The solidified lava is filled with tiny gas bubbles, and they make the surface rough and grippy underfoot.

Despite the beauty of the pools, this corner of Lanzarote had an unshakeably eerie aura. The main road is conspicuously large in its wasteland surroundings, boasting wide pavements, lamp posts, and space for palm trees. It has clearly been built in the expectation that Playa Blanca will expand – an expectation that is quietly mocked by a looming, abandoned hotel at the edge of the cliffs. This huge, empty shell was constructed in the 1970s as part of a planned golf resort, but for unknown reasons (potentially a lack of planning permission, or lack of grass), the project was never finished. The place is so isolated, and so enormous, that it looks unreal – totally out of touch with its surroundings. It’s the corpse of a capitalist dream, and it leaves the area feeling decidedly ghostly.

Visiting the Timanfaya National Park

The first thing to know about Timanfaya National Park is that it is nothing like any UK national park – and not just because it’s covered in solidified lava. Timanfaya is quite possibly the most protected area that I have ever visited. It is illegal to stray from roads and footpaths, any loud noise is prohibited, picnics are forbidden, and putting a rock in your pocket is a capital offence (slight exaggeration on this last one). The reason for these rules is obvious: Timanfaya is home to the remains of an eruption that was culturally and environmentally significant. This is a delicate and unique habitat, and its pristine condition has already been tarnished by the construction of roads and vineyards. With tourism booming, the last thing this place needs is millions of people dropping litter and stomping on the wildlife. The Timanfaya region is a product of nature’s most violent and most fragile processes acting side-by-side, and it deserves to be preserved.

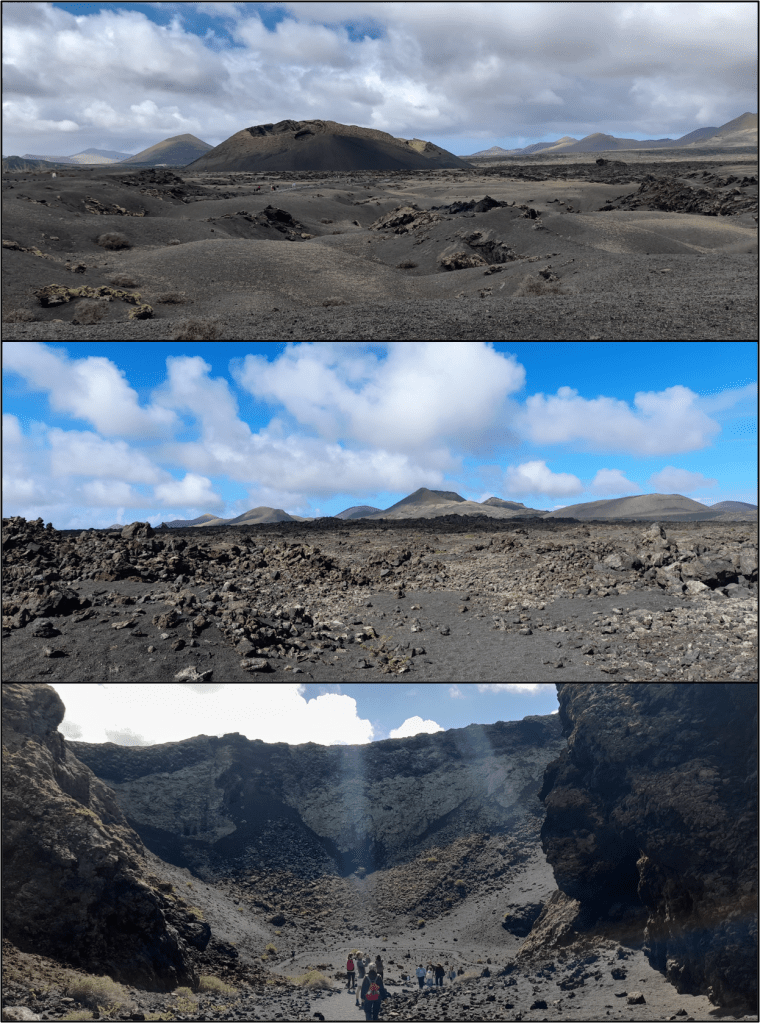

The most striking aspect of this landscape is the sheer volume of lava. It stretches as far as the eye can see, forming an unbroken carpet of black, angular boulders. Trying to walk over it would be foolish, if not impossible, because although it looks smooth and continuous from a distance, up close you realise that the lava field is riddled with cracks and valleys – the remnants of wide, sinuous channels which carried lava to the sea. Its surface consists of sharp, contorted lumps of basalt, which adopt a range of forms from streaky, striated plates to upstanding, coral-like protrusions. Once you’ve become more accustomed to the landscape, you’ll start to notice that there are subtle variations in its texture; some sections can appear smooth, or creased, or stacked like a toppled house of cards.

Standing over the lava field are dozens of conical mounds, all of different sizes and shapes and colours. Some of the cones are a deep, absorbing black, while others are a rusty brown, and some are even vivid red. Some are perfectly conical, while others are a complex mess, and some are crescent-shaped, with gaping holes where their walls collapsed. From a distance, you might assume that these cones are solid rock, but up close, you’ll see that they are simply piles of rough, pea-sized gravel, tens of metres high.

Perhaps the most staggering aspect of this landscape is the speed at which it formed. The dark sea of lava and the dozens of volcanic cones all formed between 1730 and 1736, in a series of voluminous eruptions. Before then, this region looked just like the rest of the island.

Caldera de Los Cuervos

At the edge of the Timanfaya region is the Caldera de Los Cuervos. This is one of the most popular cones, because it has a nice, easy footpath that takes you around the outside, then down through a gap in the walls and into the crater. You get to stand right in the middle, where lava once formed a bubbling pond.

As you walk around the cone, you’ll see that the surrounding lava is blanketed by a layer of gravelly material called “tephra”. This layer is mostly composed of fragments smaller than peas, but some chunks are considerably larger, up to the size of rugby balls, and these often contain huge, green crystals, which can be several centimetres long. These crystals formed within magma many kilometres beneath the ground, and they were carried upwards rapidly when the eruption began. The Caldera de Los Cuervos was actually first cone to form; an eye-witness account from 1730 describes the onset of the eruption, and how lava flowed from this cone all the way to the sea.

The cone that we see today grew rapidly, within days to weeks of the eruption commencing. Lava was launched into the air like a fountain, creating tiny globules of molten material that solidified before they landed. These globules form the tiny tephra grains that piled up into the cone, and which blanketed the surrounding landscape. Over time, the cone grew taller, allowing the lava to form a pond inside it. You can still see layers of solidified lava plastered against its interior walls. Eventually, the pressure of the lava inside caused a portion of the walls to collapse sideways, releasing a tide of molten rock. Incredibly, the undermined section of wall remained largely in one piece, and you can still see it today, standing like an island a hundred metres away, where it was carried by the rush of lava.

Caldera de Los Cuervos is also a fantastic place to see Timanfaya’s delicate ecosystem. At first glance, it might appear that nothing lives in this harsh environment. However, the bare rock is speckled with pale green lichen, and small cracks and crevices house tiny succulent plants and bushes. It has taken three hundred years for these plants to establish themselves, and they live a perilous existence without much water or soil. This is one of the main reasons to stay on the paths; all it would take is one crunching footstep to upend hundreds of years of ecological progress.

The 1730-36 eruptions

Now seems a good place to provide some context for the 1730-36 eruptions. Lanzarote has only erupted twice in human history, but these have been the largest-volume eruptions on the Canary Islands. Over six years, this corner of Lanzarote was repeatedly cracked open by fissures that released vast volumes of lava. More than 30 cones formed, and the lava destroyed 26 villages, burying the most fertile land. The resulting famine forced the majority of people to leave the island.

The fissure that formed Caldera de Los Cuervos released lava for many weeks, which spread north and west until it reached the sea. There was a brief hiatus in activity, and then a new fissure opened in June 1731, beneath the sea 14 km to the west. From here, activity migrated east, forming a chain of small cones that wiped out villages. Then, in early 1732, activity stopped migrating. Eruptions concentrated around the Timanfaya volcano for several months, building a complex edifice. However, there are no eye-witness accounts beyond this point, as most people had left the island. The last eruption was in spring 1736, occurring in the eastern end of the region, and it lasted only 10-15 days.

To really understand the devastation caused by these eruptions, try to imagine what the land looked like before the lava arrived. There were villages here, and hundreds of fields, all of which were buried in the space of six years. The first eruption must have felt like the end of the world to these people, but to have fissures open up again and again would have caused unimaginable anguish. You can’t help but wonder what would happen if a fissure opened today – which it feasibly could, as the island is still volcanically active. More people live here now than ever before, and although the islands are monitored, and there are systems in place for evacuations, there is still virtually nothing we can do to halt or divert lava flows of this volume and duration. Just look at the destruction caused by eruptions in Iceland, or on the neighbouring Canary Island of La Palma in 2022. It would be chaos.

Why are there volcanoes on Lanzarote?

The Canary Islands are all volcanic in origin, and although the source of the magma is debated, it is widely believed to come from a hot plume within the Earth’s mantle, which provides a steady supply of molten rock. Lanzarote and Fuerteventura are the oldest Canary Islands, and they form the crest of a huge pile of volcanic material that has been growing over tens of millions of years. This pile of lava is 4 km tall when measured from the ocean floor, and its top first protruded above the waves 20-30 million years ago.

The volcanic activity on Lanzarote isn’t focussed into one central conduit. It doesn’t have a big, conical volcano like Mount Teide on neighbouring Tenerife. In fact, you might have noticed that I’ve been banging on about “cones” rather than “volcanoes” throughout this post, and that’s because the generally accepted definition of a volcano (if there is one) is that it should have a structured magmatic plumbing system. The cones on Lanzarote don’t fit this definition, because they each erupted once, and won’t erupt again. If anything, they are just many tiny vents from a volcano that is so large (and largely underwater) that we can’t comprehend it.

So how does the magma reach the surface, if not through a central conduit? The answer can be seen in the organisation of the cones. They form rows across the landscape, and these rows trace the paths of fissures that once opened. When there isn’t an open conduit available, the most efficient way for magma to ascend is as a blade-shaped crack, which fractures upwards through solid rock. When these magma-filled cracks arrive at the surface, they slice open the landscape and eject curtains of molten rock into the sky. Some parts of the fissure permit higher magma flow than others, so activity focusses to these points, and these places are where the cones start forming, and where long-lasting lava flows are emitted.

Hopefully this volcanological section was of interest! Now I’ll get back to the pretty photos.

Caldera Blanca

If you want to climb to the top of a volcanic cone on Lanzarote, I would highly recommend Caldera Blanca. It has a huge crater over one kilometre in diameter, and offers superb views over the 1730 lava field. It is just outside the national park, meaning that you can walk here without a guide, and there is a relatively easy path leading to its base. From there, a narrow path leads right up to the rim of the cone, then on to the summit – although I didn’t make it quite that far. It was incredibly windy on the day I climbed up there, and the narrow rim of the cone has steep drops of a few hundred metres on either side. Combining my tragic lack of balance with treacherous terrain is a recipe for disaster, so I played it safe, gawped at the view for a while, then headed back down.

If Caldera Blanca looks different from the cones in the national park, that’s because it’s much older – tens of thousands of years old, in fact. It has weathered far more than its younger neighbours, which has given it a white outer skin, hiding the fact that this cone is made from tiny black pieces of tephra, just like the rest. However, you can also find huge, rounded lumps of rock buried here, some of them as large as sheep (which are a perfectly acceptable unit of measurement). These boulders were launched into the air during the Caldera Blanca eruption, which should give you some idea of the energy involved. The size of this cone, too, attests to a more violent formation history – probably due to an interaction with groundwater, which would have created huge volumes of steam when the magma arrived.

Timanfaya Coast Path

The only hiking trail in the national park that you can access without a guided tour is the Timanfaya Coast Path. This takes you along the edge of the solidified lava field, where the lava once inundated the sea, and where the sea is now inundating the lava. Lanzarote is a windy place, and the waves here are large even on a calm day. When we walked the coast path, the waves were a few metres tall, and when they crashed against the basalt cliffs, the noise was incredible: you could feel the thuds reverberating in your lungs.

Initially, the coastal path crosses a much older lava flow, which is tens of thousands of years old. The layers of lava have eroded to produce some curious formations, including arches and overhangs. One of the reasons that the thudding of the waves is so loud is because the ground is largely hollow; even the most solid rock contains thousands of gas bubbles, and the layers of lava are separated by horizons of unconsolidated rubble from the top of each flow. The flows themselves are riddled with hollow tubes, some of which have caved in, providing a glimpse into the depths.

One of the strangest features I found on the coast path were a series of tiny “tubelets” – hollow conduits that were only about half a metre in diameter, but up to tens of metres long. I’m not 100% sure how these tubelets form. Big lava tubes form beneath the surface of deep lava flows, like the Cueva de Los Verdes in last week’s post – but these little tubelets protrude above the surface, lying like spaghetti (or rigatone?) across the layer beneath. They almost look like candlewax dribbles, as if they poured forth relatively quickly and solidified rapidly. Intriguing indeed.

In summary…

That concludes my Lanzarote adventures! You may have noticed that I avoided the very touristy areas, such as the camel rides through the national park, or the visitor centre where they pour water into the ground to create an artificial geyser. While I’m sure these are great things to do, we prioritised activities which would be less crowded and less commercial. Lanzarote is so much more than an island of busy beach resorts. Our trip was exciting, interesting and awe-inspiring, with more “cool rocks” than I ever could have wished for (even if I couldn’t take any of them home).

Happy reading, and have a lovely week!

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.