Hello readers! This week’s post is a response to a reader request. Harry (aged 27) has asked me to investigate the feasibility of a hedgehog running over water, if that hedgehog could run very fast. Some of you may have already guessed the inspiration for this enquiry, as it relates to a franchise that is beloved by a very specific corner of the internet, and which recently received its third film adaptation. We’re talking about Sonic the Hedgehog – and after some consideration, I have decided that the films (and the games that inspired them) do fall under the broad remit of science fiction and fantasy, even if they are – how should we say – tonally distinct from the media I usually discuss on this blog. So here we go. Could Sonic really channel his inner Jesus and run on water?

For those of you that have made the wise decision to live under a rock, Sonic is a blue creature that can run very fast. He calls himself a “hedgehog”, but is almost exclusively bipedal, and unlike actual hedgehogs, he can’t swim. However, in the films and in several games, Sonic can run fast enough to cross the surface of water without sinking and drowning. This leads us to the simple question: is it really possible to run so fast that you don’t sink?

The short answer: Yes

Firstly, let’s establish how any animal could run on water. We’ve all seen insects floating around on the surface of ponds, but this behaviour is restricted to creatures of miniscule mass. The insects are light enough that they can support themselves using the surface tension of the water, which arises from the cohesion (stickiness, if you like) of water molecules. Water prefers to ‘stick’ to itself rather than to the air, and this makes the water surface behave in an almost elastic manner, providing an upwards force when insect feet create minor deformations. However, the surface tension of water is nowhere near high enough to support larger animals, no matter how fast they move.

For heavier creatures, the only way that water can support them is through drag and buoyancy. When we try to place our foot on water, the water moves out of the way – but it doesn’t move instantly. We feel resistance, which partly comes from the viscosity of the fluid (another type of stickiness, if you like – think about the difference between mud and water). Then, once we start displacing the fluid, we also feel a buoyancy force equal to the weight of fluid that we have displaced. Of course, all of this is complicated by the fact that our foot is moving, almost certainly decelerating, producing varying degrees of turbulence that make calculations unbelievably tricky. But the water provides resistance against sinking, and in theory, we can use this resistance to run over the surface.

As ever, the theoretical and computational complexity of this problem has proved no obstacle for the trial-and-error rollercoaster of natural selection. There are many small- to medium-sized animals that can run on the surface of water for short distances, with most aiding themselves by flapping their wings (even ducks can manage this), and with some managing to run entirely unsupported. One of the most surprising examples is the Basilisk Lizard – a tiny reptile which can run short distances across the surface of water on its back legs.

The Basilisk Lizard

Basilisk lizards weigh about 90 g, which makes them far too heavy to utilise the surface tension of water. Instead, they support themselves by running across the surface incredibly quickly, with a step frequency of 8 Hz (8 steps per second). Lizards of up to 200 g can generate enough force to support their body weight, although the smaller lizards find it easier, and can run further.

These little creatures are relevant to our question because they run in a bipedal manner, and because they have been studied extensively. Scientists have developed a model for the motion of Basilisk Lizards that can be applied to any bipedal creature, and there has even been published research applying the model to humans. As such, I see no reason that we can’t apply the model to Sonic (besides common sense and sensible life priorities).

How to run on water

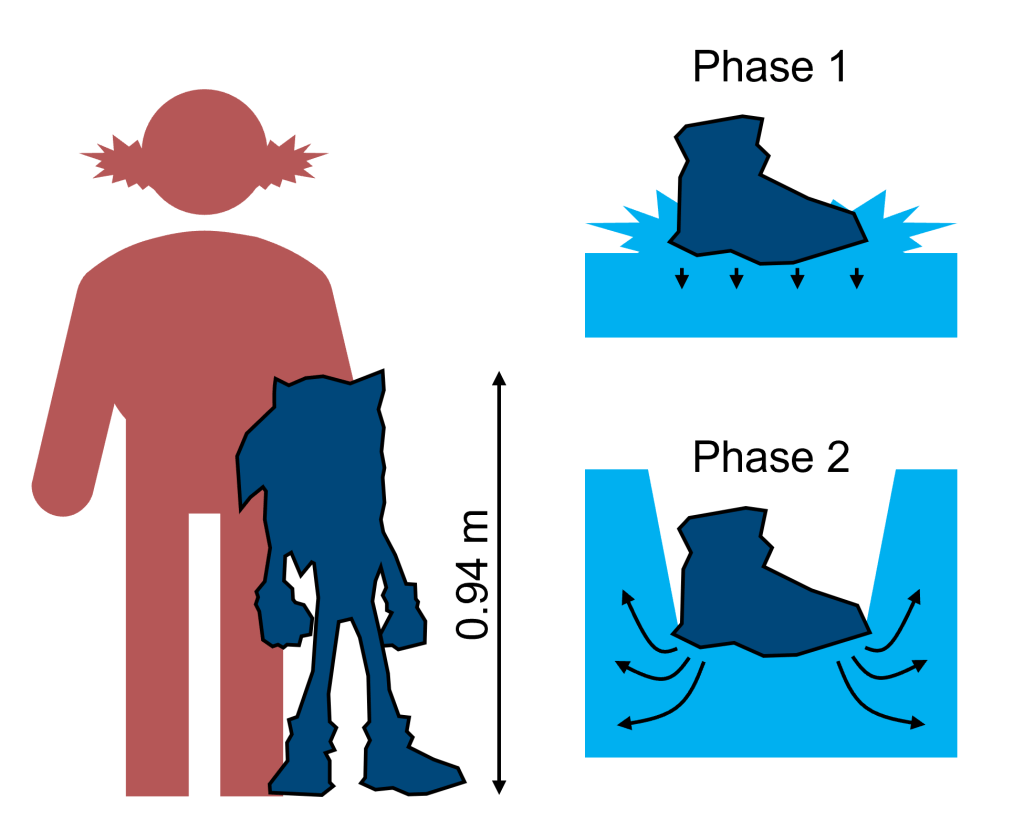

In 1996, Glasheen and McMahon presented a model for Basilisk Lizard locomotion. Each step can be broken down into two phases: phase one is when the foot hits the water surface, and phase two is when the foot pushes down through the water (the original paper calls these the ‘slap’ and ‘stroke’ phases respectively).

When the foot first hits the surface, it feels a kickback. This is phase one. Then, as the foot pushes through the water, it forms an air cavity above it. This is phase two. The foot must be retracted before the water closes in above it, or else it would take too much energy to pull the foot back out. The aim is to generate resistance as the foot goes down, in phases one and two, but to have no resistance as the foot comes up. This asymmetry provides an overall upwards force, just as the asymmetry in rowing provides an overall forwards force: the oar is pushed back through the water, providing resistance, before being pulled forward through the air, providing no resistance.

For the basilisk lizards, only 12.6-22.6% of their support comes from phase one. Most of it comes from phase two, and this proportion increases as the lizards get older and heavier. Glasheen and McMahon conducted a series of experiments, which involved filming the lizards with a high-speed camera, as well as dropping models of lizards’ feet into water at various speeds, to estimate the forces they experienced. In their conclusion, they suggested that humans could only run on water if they slapped their feet into the surface at 30 m/s, which would require around 15 times more power than the average human could manage. This led a second group of researchers to propose that humans could run on water if gravity was reduced.

A brief diversion: Can humans run on water?

The second group of scientists (Minetti et al.) used the original model to find out whether humans could run on water in reduced gravity conditions, as might be found on the Moon. They ran a series of experiments in a paddling pool, and used a harness and pulley system to simulate reduced gravity on a series of test subjects, who then attempted to run on the water surface. Thankfully, this world-changing research is open access, as it must be seen to be believed (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037300).

Based on the paddling-pool experiments, Minetti et al. established the speeds at which human feet can hit the water surface, and the total contact time for each step. They determined that humans wearing small flippers could run over water for short distances if gravity was less than 22% of its Earth value. On the Moon, where gravity is 16% of what we feel on Earth, an average human with a mass below 73 kg could run on water with just 1.7 steps per second. This life-changing discovery earned Minetti et al. the 2013 Ig Nobel physics prize (please note the “Ig”).

So, could Sonic run on water?

The model of Minetti et al. can supposedly apply to any bipedal creature, which means that we can use it for Sonic. All we need are some dimensions for his limbs, an estimate of his mass, and the frequency of his steps across the water. I have taken some values from the second Sonic film – but believe me, I did not want to spend too much time thinking about this, so take all values from here onwards with a colossal heap of salt.

By my rough estimations, Sonic is about half the height of Dr Robotnik (Jim Carrey), which makes him 0.94 m (turns out that Jim Carrey is pretty tall). Sonic’s legs are around half his height, at 0.47 m, and he’s probably around 15-30 kg, as James Marsden doesn’t break a sweat when picking him up (could it be that he doesn’t weigh anything at all?). Based on the first second of the film trailer, which I will assume is in “real time” (I know it’s not real), Sonic runs at about 12 steps per second.

The first stipulation for running on water is that the feet are extracted during phase two, before the air cavity above them can collapse. Based on the equations from Minetti et al., we know that water will start refilling the cavity in 0.27 seconds (this post will have an appendix containing all relevant calculations, if you’re honestly interested). If Sonic is running at 12 steps per second, this means that each step takes 0.083 seconds – which gives him plenty enough time to avoid his feet becoming swamped. That’s the first hurdle dealt with.

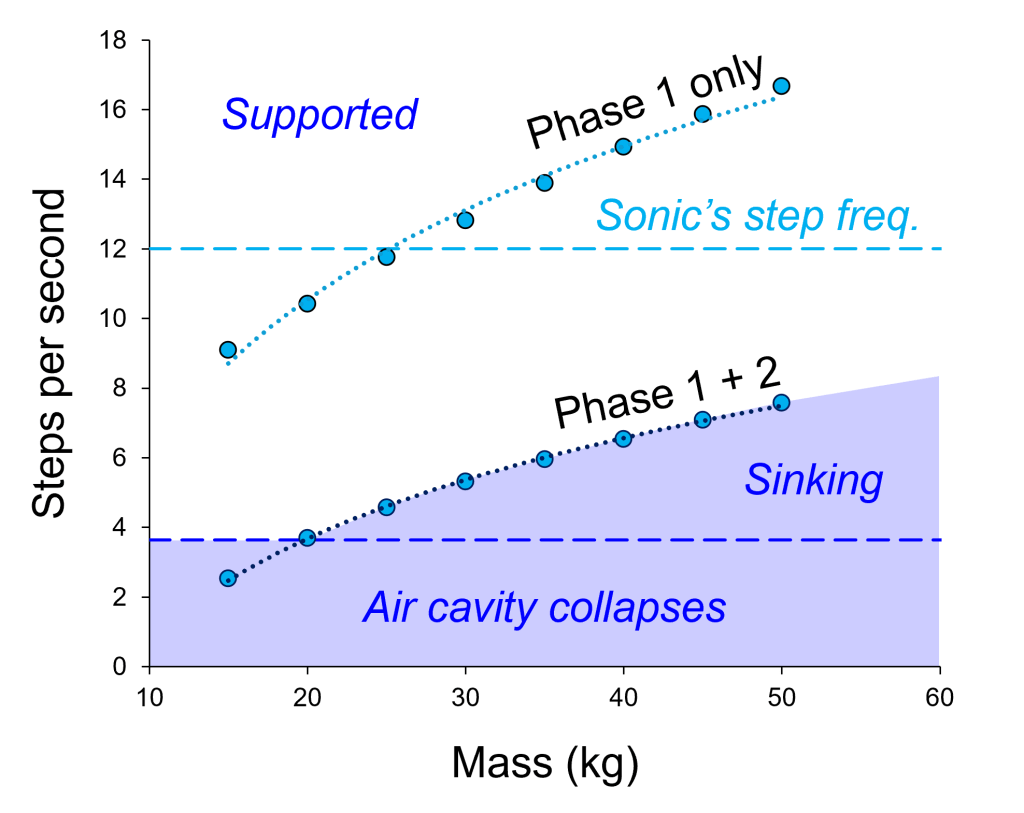

Using the Minetti et al. equations, I calculated the minimum step frequency required to keep various masses afloat, based on Sonic’s dimensions. I found that if Sonic is between 15 and 30 kg, then 12 steps per second should be more than enough to keep him afloat. The general rule is that the heavier you are, the faster you need to run – and given that Sonic is much smaller and runs much faster than a human, he doesn’t require reduced gravity to avoid sinking.

HOWEVER…

When Sonic is depicted running over water, his feet hardly enter the water at all. This is in stark contrast to the Basilisk Lizards, or the participants in the Minetti et al. study, who derive most of their uplift from phase two. It appears that Sonic only utilises phase one of the model, and so I re-ran the calculations and excluded phase two. This greatly reduces the uplift associated with stepping through the water, meaning that a greater number of steps are required to stay afloat.

Using phase one alone, Sonic would find it harder to stay on the surface of the water – but he might still manage it. Provided that he is less than 25 kg, he could just about support himself by running at 12 steps per second. If he is any heavier, this would not be sufficient to stop him from sinking.

The figure below feels far too complicated for such a stupid problem, but here we go:

The lowest horizontal dashed line (dark blue) marks the minimum step frequency required to run on water. Any slower than this, and the air cavity above the foot would collapse inwards before the foot could be extracted. The upper horizontal dashed line (light blue) shows Sonic’s actual step frequency, as shown in the film. The lower curve of points is calculated from phase one and two combined, whereas the upper curve of points is from phase one alone, which is what we see in the films. Any step frequency below these curves would lead to Sonic sinking, and any frequency above these curves allows him to remain supported.

In summary…

Many thanks to Harry for sending in this request. I hope this answered your query.

It appears that Sonic can run fast enough to stay afloat on water – although it should be noted that the models I used make no reference to forwards motion, or to the energy expended for remaining upright. Further research on Basilisk Lizards found that they spend a great deal of energy kicking sideways in order to maintain their balance, and that they make extensive use of the walls of the water cavity in phase two. Given that Sonic is only utilising phase one, and avoids making a cavity at all, it is unclear how he is propelling himself forward. The water surface won’t be providing much friction, so it seems infeasible that he could be moving forwards without getting his disgusting humanoid toes wet.

So, if that was all you needed to know, stop reading here! The next section contains the details of how I calculated everything, and the list of papers that I read along the way. I recommend looking at the first figure from the Minetti et al. (2012) paper, and looking up some videos of hedgehogs swimming. Happy reading, and have a lovely week!

Calculations…

Our first stipulation is that the foot must be pulled free from the water before the air cavity above it collapses inwards. The time taken for the air cavity to collapse is

t_max = 2.285 * (R_eff / g) ^ 0.5,

where R_eff is the effective radius of the foot, and g is gravitational acceleration. The only way that anyone could run on water is if the duration of an individual step is less than t_max. This means that the minimum step frequency required for running on water is

f_min = 1 / t_max.

The model from Minetti et al. (2012) is designed to be applied to animals of different sizes, including humans. They approximate the animal as a vertical cylinder (mass M, density D, radius R, height H) with a base containing two half-circles that act as the feet. These half-circles extend for a distance P, mimicking the feet pushing against the water.

The effective radius of the two half-circle feet is

R_eff = R / (2 ^ -0.5).

In order to avoid sinking, the total impulse from phases one and two (Imp_slap + Imp_stroke) must be greater than the weight of the creature over the duration of its step, so

Imp_slap + Imp_stroke > M * g * t_step.

The slap impulse from phase one is given by:

Imp_slap = (4/3) * (R_eff ^ 3) * D * u

where u is the velocity at which the foot hits the water. This is calculated as

u = P / t_step,

approximating the velocity as the leg length over the step duration.

The stroke impulse from phase two is given by:

Imp_stroke = 0.5 * pi * C_drag * D * (R_eff ^ 2) * u * t_step * (u + g * t_step).

The drag coefficient, C_drag, is taken to be 0.703. This is likely to be another source of error, because we don’t know the drag coefficient of Sonic’s feet. And quite frankly, I don’t want to think any more about Sonic’s feet, so we’ll just leave this as is.

Finally, by adding Imp_slap and Imp_stroke together, you get the total impulse. Or, in the case of Sonic, we assume that the impulse from phase two is zero.

Articles that I used for calculations:

Glasheen and McMahon, 1996. A hydrodynamic model of locomotion in the basilisk lizard. Nature, 380(6572), pp.340-342. https://doi.org/10.1038/380340a0

Glasheen and McMahon, 1996. Size-dependence of water-running ability in basilisk lizards (Basiliscus basiliscus). Journal of experimental biology, 199(12), pp.2611-2618. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.199.12.2611

Minetti et al., 2012. Humans running in place on water at simulated reduced gravity. PLoS One, 7(7), p.e37300. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037300

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Clayton Calculates: The feasibility of a hedgehog running over water”