Hello readers! A few weeks ago, I was lucky enough to spend a week in Crete, Greece. I knew very little about the island before going, but there was one place I really wanted to visit: the Samaria Gorge. Crete has dozens of deep, narrow gorges cutting through its mountains, but the Samaria Gorge is by far the largest and most famous. It can only be visited by following a 16-km-long hiking trail down the full length of the gorge, from the mountains to the sea. The route is walked by thousands of visitors every year – although its length, technicality and early opening hours attract only the most adventurous tourists.

I’ll use the next post to talk about my experience in Crete in general, including the food, the beaches, and the crazy road etiquette (or lack thereof). But this post will devoted entirely to the Samaria Gorge, which was unquestionably the highlight of my visit.

Route overview

The route was quite complex, involving a mix of driving, walking, ferries and buses – so to make this post easier to follow, let’s start with an overview of the day.

The Samaria Gorge walk starts at Xyloskalo, at an elevation of 1230 m. You park your car at the visitor centre and café (€5), where you must buy a ticket for the bus that will bring you back at the end of the day (€7). You then buy a ticket to enter the gorge (€10) and start the descent. The gorge is about 16 km long, and you follow it all the way down to the sea. At the end of the gorge is the village of Agia Roumeli, accessible only on foot or by boat, where there are several restaurants and shops. You then take a ferry from Agia Roumeli to the village of Sougia (€15), where you catch the bus all the way back up to Xyloskalo, to reunite with your car and head home.

There are other ways of doing the hike (some people spend the night in Agia Roumeli and walk back up to Xyloskalo the next day), but this is what I did – and to my understanding, this is the most common route.

Leaving before sunrise

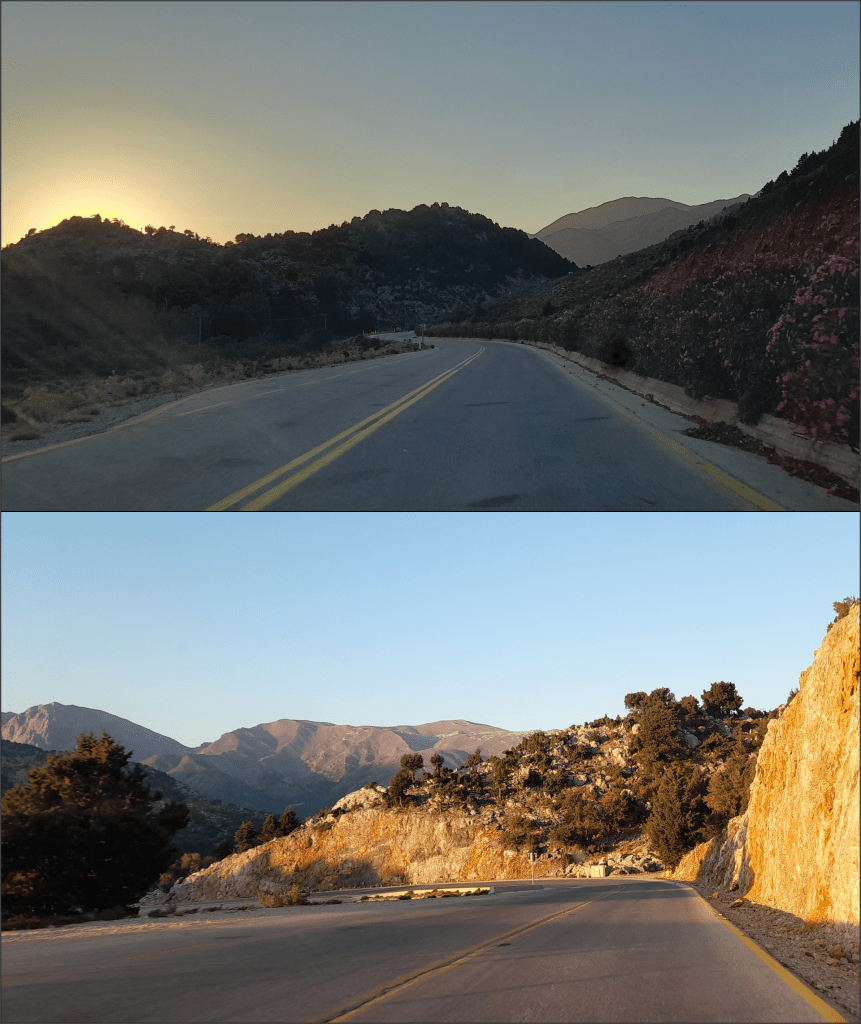

Entrance to the gorge is only permitted between the hours of 07:00 and 13:00, and we aimed to arrive as early as possible in order to beat the buses of tourists from Chania. The gorge soon gets busy, and we knew that the easiest way to avoid the crowds was to stay ahead of them. Starting early also limited the time we had to spend in the midday heat – and it removed any stress about missing the ferry! So, we got up before the sun rose, and drove into the hills.

The journey up to Xyloskalo was an adventure in itself. As it was so early in the day, we had the winding mountain roads all to ourselves. We watched the sun rise over Crete, as every wrinkled valley and craggy hilltop was captured by a beautiful contrast of rosy light and dark silhouettes. The pale, rocky outcrops gained a golden hue, while the deep, sheer-sided valleys remained caught in hazy shadow. We saw valleys filled with vivid, magenta wildflowers and dense, towering pines, and drove though villages that clung to the mountainsides, their buildings looking out over precipitous drops. The road was, for the most part, wide, quiet, and very safe – although we had to wait a couple of times for sheep to move out of the way. Besides us, they were the only ones awake.

Eventually, the mountains parted to reveal a wide, flat basin. This was the village of Omalos, an oasis of green pastures and apiaries 1000 m above sea level. Most of the village buildings appeared to be hotels, offering a base from which tourists can head up into the Lefka Ori (White Mountains). At the southern edge of the Omalos basin, a huge, silver peak with vertical walls had risen into sight. This was Gingilos – the commanding, sheer-sided monolith that stands at the head of the Samaria Gorge.

Starting the descent

The views at the beginning of the walk are spectacular. Gingilos dominates the landscape, but at 1960 m high, it is far from the largest mountain in the area. The ridge behind it, though less distinctive, towers at 2080 m – and to the east rises the heart of the Lefka Ori, containing the highest mountains on Crete. These uplands are entirely devoid of vegetation due to the harsh climate, and this leaves the marble, limestone and dolomite bedrock entirely exposed. The barren landscape is highly reflective, turning the mountains a blinding white under the blazing sun.

Before we set off, I wasn’t sure how difficult the hike would be. I have lots of hiking experience in northern England, but our mountains are small by comparison (Scafell Pike is only 978 m!). I had read plenty of conflicting opinions online, with some people saying it was really hard work, and others saying that it was easy. Safe to say, I was trying to go in with an open mind – and in the end, I think it was easier than many UK walks I’ve done. I’m used to fair amount of scrambling, and the distance wasn’t too bad: the hardest part was the heat and the sun. On the day I was there, the temperature was around 30 °C, and we got most difficult section out of the way in the early morning, before the sun became too strong.

It should be noted that this is not a walk for people with bad knees! In the first kilometre, we descended 500 m in elevation, and although some parts of the path were paved and well-maintained, other sections went across loose, rounded boulders, which had been polished to a shine by thousands of feet. I skidded a few times and didn’t quite fall (a miracle), but I imagine that this path has caused countless bruises and twisted ankles over the years. It’s too easy keep looking up at the mountains rather than down at your feet!

National park status

The Samaria Gorge was made a national park in 1962, with the aim of protecting its rare plants and animals. It is home to the kri-kri, a species of goat that was once widespread around the Mediterranean, but is now endangered. In 1960, only 200 goats remained in the White Mountains – and this prompted the Greek government to create the national park. Then, in 2014, the region also became a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, giving it even greater protection. According to the UN website, new endemic species are still being discovered there today. These are species that can be found nowhere else.

Because the hike goes through protected land, visitors are required to follow strict rules. There are obvious ones, such as “no littering”, but there are others that might be more surprising to UK visitors. For example, you can’t swim or even step in the water, and you aren’t allowed to relieve yourself behind secluded bushes. This is all in an effort to protect the environment, ensuring that the water remains clean enough to drink. And thankfully, these environmental restrictions mean that there are toilets available at each of the major rest stops – saving everyone the stress of trying to find a suitably dense shrub. It does, however, make the environment feel less wild, as it is so tightly controlled.

The signs around the national park also specify that you can’t collect rocks (fair enough – I restrained myself) or plants. It also has a specific icon to make it clear that you must not, under any circumstances, shoot the goats. And as much as I chuckled at the cartoonish nature of this sign (which appears to show a cyborg man with a gun for an arm), its existence suggests that goat-shooting is still a problem in the area. I can’t fathom why people would shoot the goats. You would have to hike 16 km, probably scrambling onto treacherous terrain, and if you managed to shoot a goat, you would then have to carry it all the way back out of the gorge. It seems like a lot of effort. Does kri-kri taste that good?

Thinking about geology…

As you climb down from Xyloskalo, there are plenty of yellow warning signs telling you to move quickly. The reason is pretty obvious: huge sections of the valley sides have collapsed, or are in the process of collapsing, creating a high risk of rockfalls. Whenever it rains, the rocks start crumbling, causing enormous boulders and streams of mud to cascade to the valley bottom. For this reason, the gorge is only open in Crete’s dry season, between May and October – but when you look at the giant rocks in the riverbed in the base of the gorge, you realise that most recent landslides, even those in winter, are relatively small-scale events in the gorge’s long history. In the past, boulders the size of houses have tumbled down from the valley walls, only to be bashed and rounded by the force of the water. Each one of these rocks is on a slow journey down to the sea, with every storm wearing them down a bit more, allowing the water to drag them a bit further.

The rocks of the Samaria Gorge are ancient, laid down at the bottom of the Tethys Sea 140-225 million years ago. Since then, they have been crushed, folded and uplifted by powerful tectonic forces – as evidenced by the twisted, crumpled layers in every cliff face. The carbonate chemistry of these rocks means that they are slowly dissolved by rainwater, and this has led to the formation of complex cave systems in the neighbouring mountains, some of which are 1000 m deep. This unique geology, combined with the forces of powerful flash floods, has allowed the gorge to be carved out over millions of years.

Samaria village

Around 6 km from Xyloskalo, still 400 m above sea level, another major tributary joins the river. Here, where the gorge widens out, you will find the small, deserted village of Samaria. This village, which is right at the heart of the gorge, had been inhabited for thousands of years due to its sheltered and easily defensible location, but its final residents left in 1962. According to Wikipedia, the village was “abandoned” when the national park was created – but I can only assume that the villagers were forced to leave, rather than choosing to move. Most of the buildings are still standing, and some are used by the park rangers.

Today, the village is home only to goats. It still has orchards, vineyards and fields, but many of these have been adapted to provide shaded picnic areas for the hikers passing through. When we arrived, we saw a kri-kri sitting on top of one of the benches – which looked very cute and picturesque until we saw that it had left a pile of “goat produce” in the middle of the table.

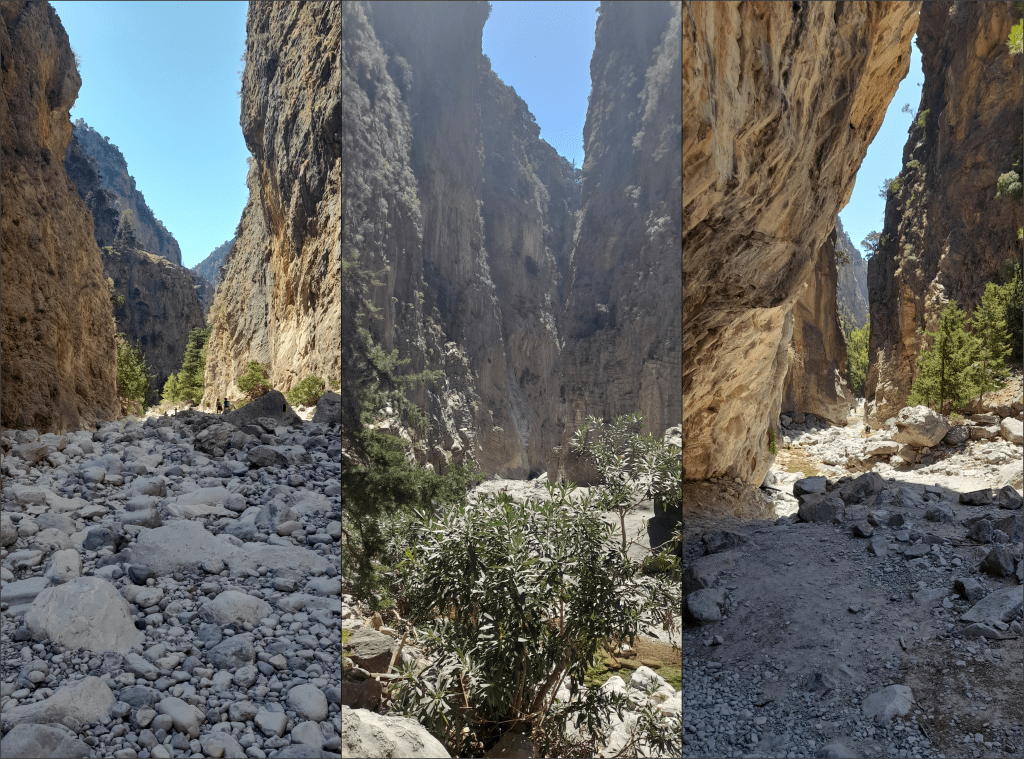

The gorge gets narrower

Having eaten our lunch in the village, we carried on, heading into the narrowest, deepest section of the gorge. We knew that the gradient would be minimal from this point forth, but we were wrong to think that the going might get easier. The path took us into the rocky bed of the gorge – where a river would have flowed, had there been any water. Every boulder was rounded and smooth, carrying the scars of raging flash floods. You could tell the age of the path by how shiny the stones were: where the path had been there a long time, the rocks had been polished by tens of thousands of feet. Some sections, however, were dry and dusty – suggesting that the riverbed had recently shifted in a flood.

There was also plenty of evidence of landslides and rockfalls, with some of the cliffs blanketed by heaps of debris. Warning signs appeared more regularly, urging visitors to move quickly through particularly risky sections. On the day we were there, it hadn’t rained in some time, and the rocks were bone dry. Still, we heard the tinkling echoes of tiny rocks raining down, showing that parts of this landscape are just one thunderstorm or one clumsy kri-kri away from collapsing.

The Gates

The gorge gets narrower and narrower towards the coast, with the walls even starting to overhang the riverbed in some places. Crack-like chasms cut in on either side, creating narrow corridors to the towering peaks. These fissures feed the gorge when it floods, but in August, they were dry and trapped in shadow, opening up a vivid cross-section into the mangled innards of the mountains. We could see thousands of layers of rocks, all sliced and warped and folded, stretching through hundreds of metres of smooth cliffs.

Eventually, the gorge narrows to a width of only three or four metres, with unbroken cliffs dozens of metres tall stretching up on either side. This section is known as “The Gates” or “Iron Gates” depending on your guidebook. I’ve seen varying estimates for the height of the chasm, from 300 to 500 m, and I suppose it depends on your definition of “the top” – whether that’s the vertical cliff section, or the towering peaks beyond. Either way, it’s impossible to gauge the height by looking up from below.

Out to Agia Roumeli

Beyond The Gates was a café serving beer and fresh orange juice. This marks the border of the national park, where the gorge finally widens out – becoming wide enough to house a road, in fact. There are a few farms here, still lived in, with vineyards and orchards and fields of sheep. There was even a small bus carrying weary tourists down to the sea – but we knew we could manage the final 2 km. Why come this far only to get a bus?

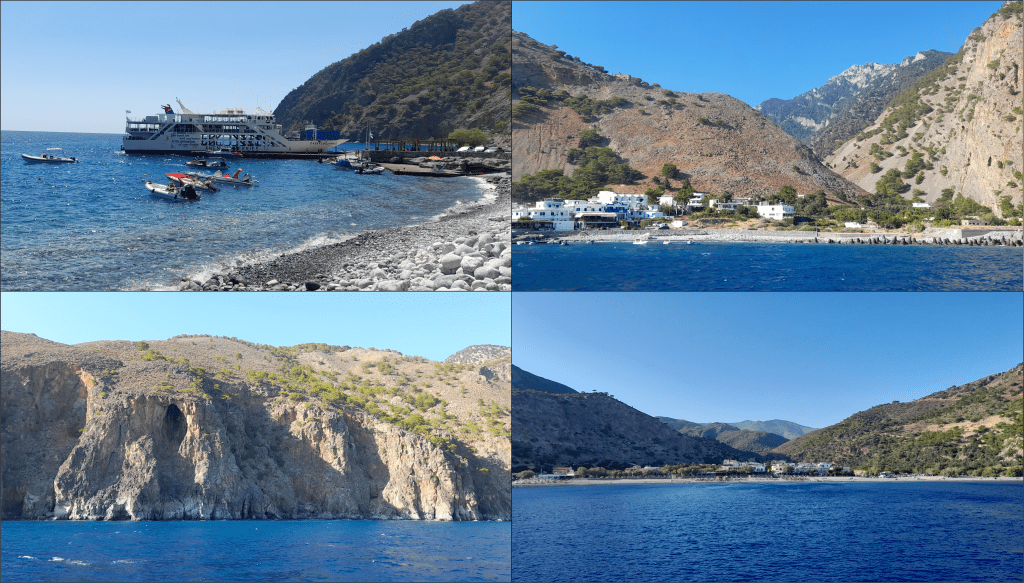

When we arrived in Agia Roumeli, we saw the ferry waiting for us. We had made it there at 15:00, a whole two and half hours before the boat was scheduled to leave, and well ahead of the crowds. With plenty of time to relax, we headed into one of the local restaurants for some food, where I had some lovely stuffed vegetables. I also got a good chuckle from one of the menu items being listed as “goat in the oven” (an amusing translation of “roasted”, presumably – and hopefully not a cyborg-harvested kri-kri).

Agia Roumeli is a tiny village, accessible only by boat or on foot. According to the Greek Wikipedia page, it only has 57 residents – which is fewer than you might guess from the size of the ferry. A boat this big is only required to house the sheer number of tourists who come pouring through the gorge in the summer months. We had started the walk so early, and made such quick progress, that we hadn’t found the route to be too busy. Only now, when people were starting to accumulate in front of the ferry, did we realise quite how crowded it must have been behind us.

A word of warning…

It’s at this point that I must shamefully admit that I had heat exhaustion. Don’t ask me how: I’d worn a hat with wide brim all day, drank litres and litres of water (using every spring and then every toilet along the route) and stuck to the shade wherever possible. I don’t take chances with the sun, due to my borderline vampiric complexion (I have even managed to burn in March in the UK), and for most of the walk I felt fine. It was only when I stopped and considered eating a cooked meal that the queasiness set in. Suddenly, I was hit by a crushing headache.

When the restaurant owner noticed that I hadn’t eaten my food, and that I was looking a bit peaky (my face had turned the colour of Melton Mowbray’s finest pork pie), he stepped in and saved the day. He brought out a sachet of electrolytes and a glass of water, and on seeing my blatant confusion, explained that this was how to deal with heat stroke. Now, I’ll be honest – I have always thought that “electrolytes” were just some nonsensical buzzword used to sell energy drinks. However, once I Googled the contents of the sachet, I learnt that electrolytes genuinely help your body absorb water. Even the NHS recommends them for cases of heat exhaustion. So, I gulped down the chemicals, and within minutes I was feeling better. I promised the restaurant owner that I would give him a glowing Google review, and I promised myself that I would add electrolytes to my hiking first aid kit.

Could I have avoided heat exhaustion? I don’t know. It was 30 °C, and I was doing fairly strenuous exercise for several hours. Perhaps it couldn’t have been avoided. But it was especially galling because my partner was perfectly fine – and they had gone without a hat and worn a black shirt all day. Clearly I am just a weakling.

Ferry to Sougia

Having got over my heat-induced queasiness, I was forced to confront the mother of motion sickness: the ferry. I would say that the sea wasn’t choppy, but there was a fair bit of swell. So, I sat near the edge of the boat, in the open air and in the shade, and kept my gaze focussed on the horizon. The views were astounding: the water was bright blue beneath the cloudless sky, and the pale cliffs were hundreds of metres tall in places, dotted with caves. There were secluded beaches, accessible only by boat, some of which had some very adventurous visitors. Clearly, if you want to escape the crowds on Crete, you have to be prepared to kayak several kilometres.

We reached Sougia an hour or so later, where we saw dozens of buses lined up by the ferry port. We found our way onto one of several coaches heading back up to Xyloskalo, and there followed one of the most tense bus journeys I have ever experienced. I’ll save my commentary on Cretan drivers for the next post, but let it be known: Cretan bus drivers fear the brake pedal more than they fear heights. The roadmap of this region looks like someone released a horde of drunken snails onto the page: the roads cling to the sides of deep, tortuous valleys, and inch their way up into the mountains via a series of hairpin bends. The views from the bus were incredible – but it was better to focus on the distant White Mountains than to risk looking down past the dented crash barriers at the side of the road. You’d think our bus driver was trying to set a speed record, but he was barely keeping up with the bus in front.

I tried taking photos during the bus journey, but looking back at them later, I saw that they were all hilariously motion-blurred. We drove past dozens of olive groves, and saw hundreds of tiny white cottages sticking like limpets to the sheer slopes. I also saw more beehives than I have ever seen in my life – probably over a thousand of them by the end of the journey. The road got steeper, to the point where the bus driver started turning off the air conditioning whenever he thought he needed a little extra oomph (he categorically did not need it). Eventually, the road reached an incredible ridge connecting two mountains, which offered views to the sea on the northern and southern sides of the island. This road should be a tourist destination in itself. Best enjoyed at slightly slower speeds.

The journey ends

After half an hour of terrifying twists and turns, we were reunited with our trusty hire car back at Xyloskalo. As a point of reference, Google Maps thinks the journey from Sougia should take 55 minutes by car. The bus (I repeat: BUS) managed it in 45. Which means that our driver was averaging (I repeat: AVERAGING) 50 km/hr. Never was I so happy to get back in a passenger seat on the wrong side of the road.

As we drove home, the sun was setting. We had to stop for a sheep to cross the road. Then we had to wait for the rest of the sheep to cross the road. But thankfully, neither me nor my partner made the rookie error of trying to count them – so we were wide awake to watch the sun go down.

In summary…

If you are ever in Crete, and have the fitness and resilience to manage a long, downhill hike in hot weather, the Samaria Gorge is not to be missed! I did not find it too challenging, and I would class myself as a fairly average fell-walker by UK standards. The walk was busy, but nowhere near as busy as the Peak District or Snowdon. I think setting off early was the right call: we kept ahead of the crowds, and only saw them once we all piled onto the ferry at the end of the day.

In the next post, I’ll talk about a few other, smaller activities that I got up to during my visit, as well as some more general comments about food and beaches and roads (the bus driver was not alone in his need for speed). Happy reading, and have a lovely week!

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “The Samaria Gorge (Crete: Part One)”