Hello readers! Last weekend I read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis, having not picked up the book since I was about ten years old. This book is possibly the first fantasy story that I ever read, and I have fond memories of it – and for the Chronicles of Narnia as a whole. With the recent news of an upcoming film adaptation of the series (directed by Greta Gerwig, no less) I was interested to see whether I would appreciate this book as an adult, and whether I could still recommend it to children.

SPOILER WARNING!

There will be minor spoilers ahead. But most of you have read this book before, right?

Some historical context…

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was published in 1950. Lewis wrote it for his goddaughter, Lucy, to whom the book is dedicated in a lovely foreword, and after whom the main character is named. The idea of an adventure involving four siblings first came to Lewis in 1939, when children were evacuated from London due to bombing in WWII. However, it took ten years for the novel to reach its final form, with talking animals, mythical beasts and magical wardrobes. In fact, it’s interesting that Lewis bothered to write a story for children at all, because he had no children of his own. He worked as a professor at Oxford university, and he wrote the Narnia books in his evenings, as a hobby. Somehow, despite never testing his stories on a young audience, he managed to capture childhood fascination and wonder – and the books were incredibly successful.

The allegory allegations

As soon as the books were published, critics accused Lewis of crafting an allegory to push Christian values onto unsuspecting children. They took particular issue with Aslan, whom they interpreted as an allegory for Jesus. Lewis denied that the books were allegorical; instead, he claimed that The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was a “supposal”, asking how Christ would appear in another world. And Lewis probably should have had the final say in this matter, given that his academic area of expertise was allegorical literature. To him, Aslan was not an allegory for Jesus; Aslan was Jesus, manifested in a fantasy realm. However, such definitional quibbles would probably be lost on children, and Narnia is often regarded as an allegorical tale. After all, a child doesn’t have to be a genius to draw parallels between Aslan and Jesus.

To me, however, the more important question is whether The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is a good fantasy story. Is it still a gateway to the genre?

Plot summary (a trip down memory lane for most of you)

“Once there were four children whose names were Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy.”

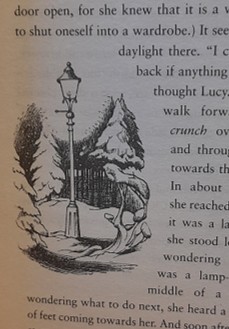

The story begins with four children being evacuated from London and sent to live with an ageing professor in a big, old house in the countryside. There, they find a wardrobe which acts as a portal into the world of Narnia, a snowy kingdom inhabited by talking animals and mythical creatures. The youngest child, Lucy, finds her way into Narnia first, where she sees an old lamppost in the middle of the snowy forest. She meets Tumnus, a faun, who reveals that the land is under the rule of the White Witch, who keeps it in eternal winter, and who wants human children brought to her.

When Lucy returns to the real world, she finds that virtually no time has passed since she stepped inside. She tries to take her older siblings to Narnia, but can’t, because the wardrobe’s powers are somewhat temperamental. Lucy’s siblings believe that she is making up stories.

Later, however, the second-youngest child, Edmund, returns to the wardrobe and ends up in Narnia himself. He meets the White Witch, and after she flatters him and feeds him Turkish Delight, he tells her all about Lucy’s meeting with Tumnus, and promises to bring his siblings to her. However, being the spiteful little brat that he is, Edmund then refuses to tell his older brother and sister that Narnia is real, and uses the opportunity to suggest that Lucy is mad.

A few days later, all four children end up in Narnia. Lucy is vindicated, and Peter and Susan are furious with Edmund. They go to find Tumnus, only to see that his house has been destroyed, and that he has been captured.

They then get lost in the snowy woods – only to be rescued by a couple of talking beavers. The beavers inform them that their coming has been foretold, and that the winter will end when four humans sit upon the four thrones at Cair Paravel, the castle by the sea. They also reveal that a lion named Aslan has returned to Narnia, and that he will set things right.

Edmund, becoming more spiteful by the minute, runs away to tell the White Witch everything the beavers said. She immediately chases them down, forcing the other children to flee for their lives, hoping that Aslan will save them. As they run, the snow starts melting, and by the time the next day dawns, spring has arrived.

They find Aslan at the top of a hill, beside the Stone Table – an enormous slab covered in runes. He rescues Edmund from the Witch, but she claims that Edmund betrayed her, so she has the right to kill him. Aslan speaks with her and prevents any conflict, and although the animals celebrate, Lucy and Susan are worried about the deal Aslan has made. That night, they see him sneaking away, and they follow him. He returns to the Stone Table, where the White Witch has him bound and humiliated by her evil creatures. She then kills Aslan with a giant stone knife. Once the evil creatures have departed, Susan and Lucy stay by Aslan’s side until morning – when suddenly, the Stone Table cracks, and Aslan comes back to life.

Aslan takes them down to the White Witch’s castle, where they free the hundreds of creatures she had turned to stone (including Tumnus). They then ride out to meet her in battle, where Aslan pounces on her and kills her instantly. The four children go to Cair Paravel and are crowned kings and queens of Narnia – and they then spend over a decade there, hunting down the last remaining evil creatures.

As adults, they go out hunting a white stag, and find themselves in the woods where the adventures began, near the old lamppost. Suddenly, they find themselves tumbling out of the wardrobe, having turned back into children, with no time having passed since they left.

First impressions on a re-read?

This book doesn’t just have Christian overtones. It has tones as powerful as a cathedral organ playing Jerusalem so loudly that your heart shakes in your chest. Somehow, as a kid, I was able to look past this, but now, as an adult, the Christianity is everywhere. You cannot escape it.

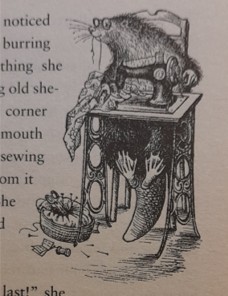

At the same time, this book is also far more pagan than I remember. The ancient Stone Table, indecipherable runes, and talk of “Old Magic” is surprisingly dark, and quite at odds with the Christian themes and childish whimsy. This is a book where Mrs Beaver gets a new sewing machine from Father Christmas. This is also a book where Aslan is bound, beaten, then stabbed by a half-giant sorceress wielding a jagged stone knife. It’s really quite jarring.

I’m not sure that I would let children read these books without some level of adult supervision. A little bit of context would go a long way, and some aspects deserve discussing – particularly the way that Lucy and Susan are consistently relegated to support roles. There are much better aspirational tales for children these days. But this isn’t meant to be aspirational; it’s classic literature, so it should be treated like a window to the past, rather than a simple story.

Writing style and whimsy

I like Lewis’ writing style. It is very accessible, and mostly written in the second person, as if he was talking directly to an audience of children. He even gives his own opinions sometimes; for example, suggesting that the best way to eat trout is as the beavers do, fried within half an hour of being caught. I love little bits of whimsy like that.

The writing is also very concise; within the first page, the children and the professor have been introduced, and we know the set-up. We know that Peter is adventurous, Lucy is frightened, Susan is optimistic, and Edmund is an all-round awful human being. The most descriptive language is reserved for landscapes and setting scenes, but even then, only the most important details are given.

“…they looked into a room that was quite empty except for one big wardrobe; the sort that had a looking-glass in the door. There was nothing else in the room at all except a dead bluebottle on the window-sill.”

I love this description. The detail of the dead bluebottle feels oddly specific, but it tells us more about that room than any specific dimensions, or colours, or smells ever could. It does all of that at once. I actually remember this capturing my imagination as a child.

The sight of the lamppost in the middle of a snowy forest, so unexplained and out of place, is magical whimsy at its finest. There is never any explanation for it – and I love that. Then, when Lucy goes to Tumnus’ house, she reads the titles of books on his shelf, which include “Nymphs and their Ways” and “Is Man a Myth?” which is a lovely bit of world-building.

I hate Edmund.

It is hard to put into words how much I despise Edmund. I don’t care that he’s a child. He’s an unforgivable, cold-hearted twerp.

When Edmund first enters Narnia, he isn’t particularly awestruck or impressed. He isn’t inquisitive. His first thought is to resent Lucy.

“Just like a girl,” Edmund thought to himself, “sulking somewhere, won’t accept an apology.”

And not only is Edmund nasty in temperament, he is also incredibly stupid. When the White Witch appears, he doesn’t realise that she is tricking him. He instantly tells her everything, including Lucy’s meeting with Mr Tumnus (which gets the poor faun arrested and turned to stone), and he doesn’t pick up on the fact that the witch is obsessed with him being one of four siblings. She keeps flattering him, and he falls for it again and again.

“There are whole rooms full of Turkish Delight, and what’s more, I have no children of my own. I want a nice boy whom I could bring up as a Prince and who would be King of Narnia when I am gone… you are much the cleverest and handsomest young man I’ve ever met.”

When the witch tries to get Edmund to bring his siblings to her, she promises that she will make them dukes and duchesses, thinking that he would be happy to see his siblings succeed. But no – this is Edmund. Her promises have the opposite effect; Edmund doesn’t want to see his siblings rewarded, because “there’s nothing special about them.”

If you were left in any doubt that Edmund is a terrible human being, he then decides to lie about Narnia in order to make his little sister appear mad. I remember hating Edmund when I was a child; I think I hate him even more now that I’m an adult.

And he gets worse. When all of them arrive in Narnia, Edmund instantly tries to convince Peter that they shouldn’t believe Lucy, and that the White Witch probably isn’t evil. When he runs away to betray his siblings, we get some insight into his thought process. We learn that he is aware of the witch being “bad and cruel” but that he still wants to be rewarded by her, and that he wants her to punish his siblings.

“He had just settled in his mind what sort of palace he would have and how many cars and all about his private cinema and where the principal railways would run and what laws he would make against beavers and dams and was putting the finishing touches to some schemes for keeping Peter in his place, when the weather changed.”

Towards the end of the book, Lewis tries to redeem this odious little character, but he has done too good a job of making him unlikeable. In the final battle, Edmund chops the witch’s wand in half – and in doing so, does more to win the fight than Peter. It is then revealed that Edmund is only a horrible human being because he had been sent to a “horrid school”. And after meeting the reborn Aslan, Edmund is suddenly “his real old self again” – not that we’re given any evidence to support this.

Edmund, in my view, remains unredeemed at the end of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. I guess we’ll find out if he becomes a decent fellow in the next book, Prince Caspian. But I don’t have high hopes.

The Christianity

I accept that Aslan is Jesus from another world. But most of the Christianity in this book is conveyed in the language and the way that characters are treated, rather than by the Jesus allegory (or “supposal”). For example, when the children first meet Aslan, he greets Peter first, then Susan and Lucy, then the beavers. This is a deliberate hierarchy, which follows Christian beliefs: men are more important than women, and humans are more important than animals. This hierarchy is problematic because it is subtle and unexplained. A child won’t necessarily pick up on the historical context, and it merely enforces a cultural belief system in a child’s imagination.

Throughout the book, humans are called “Daughters of Eve” and “Sons of Adam”, in direct reference to the Bible. So, not only does the book enforce Christian beliefs, it also requires the reader to have pre-existing knowledge of Christian beliefs. Actually, it requires quite a bit of pre-existing knowledge – a point which we’ll come back to later.

I have questions about the world-building.

I appreciate that this is a fantasy book for children, but that shouldn’t be an excuse for plot holes and poor world building. Tolkien set the bar high when The Hobbit was published in 1937 – and children are allowed to expect well-constructed worlds.

My first question is why Narnia is such a Christian nation. The animals never mention God or the Bible, so why do they have a concept of Adam and Eve? Why do they believe that humans are superior to animals, and that men are superior to women? This is never explained, so the fantasy world appears to have inherited the cultural beliefs of our world for no discernible reason.

My second question regards the Narnia ecosystem. The nation resembles the British Isles in terms of its trees and plants, yet it is home to more exotic species such as leopards, and even a kangaroo. How do they survive there? How did they get there? Another problematic example is a sheep-dog, which helps Aslan get his animal troops in order before battle. I appreciate the whimsy here, I truly do, but dogs were selectively bred by humans – so how did a dog end up in Narnia, a land with no humans?

Following on from this, I have questions about the interaction between animals. Does Narnia have a food chain? The world becomes a lot darker when you consider that the talking lions are hunting and eating the talking deer. And are any of the animals farmed? At the start of the book, Tumnus invites Lucy for tea, and serves her a feast including “a lightly boiled brown egg, sardines on toast, buttered toast, toast with honey, and then a sugar-topped cake” – all of which require dead animals or animal products. Perhaps only mammals can talk, and birds and fish are fair game? But that still means that a cow with human-level intellect had to give up her milk for Tumnus to eat his buttered toast.

I also have questions regarding the level of technology in Narnia. Cair Paravel is reported to glitter with hundreds of glass windows, suggesting a high level of technological advancement, yet Peter is given a sword to fight the witch, rather than a semi-automatic machine gun. Mrs Beaver owns not one but two sewing machines by the end of the story. Does Narnia have a smog-choked industrial district full of factories that nobody is talking about?

A non-existent magic system.

Narnia magic is unexplained and unlimited. Rules do not exist. Our first encounter with magic is when the White Witch takes a small bottle, allows a droplet to fall on the snow, and conjures Turkish Delight out of thin air. How does she do this? Don’t ask. Don’t even think about asking; there will be no answer.

Later in the book, Lewis explains that the “Deep Magic” was created by the “Emperor-beyond-the-sea”, whom we are led to believe is the most powerful being in the universe. In fact, Mr Beaver explains that Aslan is the son of the Emperor, and given that Aslan is the Narnia manifestation of Jesus, we can only assume that “Emperor-beyond-the-sea” is the Narnia manifestation of Christian God. So what the hell is “Deep Magic”?

According to the White Witch, the “Deep Magic” states that a traitor belongs to the one whom they betrayed, and that they have a right to kill them; in fact, she insists that unless she kills Edmund, “all Narnia will be overturned and perish in fire and water”. Aslan acknowledges that she has interpreted the “Deep Magic” correctly – leaving us to conclude that this “Emperor-beyond-the-sea” wasn’t particularly benign. Or fair.

Then, after Aslan miraculously comes back to life, he reveals that there is another type of magic. Apparently, the “Deep Magic” is from the dawn of time, but if the witch had looked back “into the stillness and darkness before Time dawned” she would have realised that the Stone Table can bring back people who sacrificed themselves for another. This deeper layer of magic isn’t really explained. If this is an allegory (or “supposal”) for some kind of Christian lore, it’s beyond me.

The magical species of Narnia

There are a lot of magical species in Narnia, and none of them (so far as I am aware) are original creations from C. S. Lewis. Most of them require some level of familiarity with Greek, Roman and Celtic mythology, which seems quite demanding for a children’s book.

We start with the Tumnus, a faun (half-man, half-goat), who describes nymphs (nature spirits) and even distinguishes naiads and dryads. He also asserts that “Bacchus himself” comes out in summer, to make the streams flow with wine. You know, children – Bacchus? The Greco-Roman God of wine, fertility and revelry? You’re telling me that you managed to get to the age of eight without studying Classics? You absolute plebeian.

Tumnus also describes dwarfs and giants, and we even get mention of a dragon when Edmund visits the White Witch’s castle (although the dragon is not mentioned again, even when Aslan arrives to bring the stone animals back to life). Later, we meet centaurs, unicorns, and a bull with the head of a man (terrifying). The White Witch lists off more creatures: ghouls, boggles, ogres, minotaurs, cruels, hags, spectres, and “the people of the toadstools”. I don’t know why, but leaving the toadstool people until the end of the list really cracked me up. You’re meant to end with the most impressive creature, right? And I’m out here imagining Toad from Mario dancing around the Stone Table.

Lewis also implies the existence of more evil creatures “whom I won’t describe because if I did the grown-ups would probably not let you read this book”. What is this – self-censorship? What’s happening in Narnia that you won’t tell us about, Lewis?

Later in the book, we get even more lists of evil creatures: wraiths, horrors, incubuses (ah yes, children – can you remind me what an incubus is again?), efreets (you must know, children, that this is a fire demon from Islamic folklore), sprites, orknies (magical creatures from the Orkney Isles, you stupid child – the clue is in the name!), wooses and ettins (a woose is a hairy man of the woods, and an ettin is a giant from Northumbrian folklore – are you telling me, children, that you don’t have the prerequisite postgraduate degrees for reading this book?). Oh, and there are also mermen and mermaids.

The White Witch is also revealed to be a creature, rather than human. The beavers explain that she comes from “Adam’s first wife, her they called Lilith” and that she is half giant. This reference to Lillith suggests that the animals of Narnia are somehow familiar with Jewish and Mesopotamian mythology. And again, Lillith isn’t exactly a child-friendly character…

You would have to be a very well-read child to recognise half of these creatures. And children in the 1950s were undoubtedly safer, given that they couldn’t just Google what an incubus was.

Gender roles…

One of my biggest gripes with this book, which I even remember being annoyed at as a child, is the constant sidelining of the female characters. Only Lucy and Susan help Mrs Beaver prepare the lunch. Mr Beaver and Peter caught and gutted the fish – and I guess Edmund just did nothing, because he’s an irredeemable little toad?

Lewis sometimes forgets that women exist. When the children and the beavers are eating their meal, he states that “everyone took as much as he wanted to go with his potatoes” but five lines later, he clarifies that “when each person had got his (or her) cup of tea, each person shoved back his (or her) stool… to lean against the wall”. The girls always seem to be an afterthought when he is dealing with a group of characters, if he bothers thinking about them at all.

When they first meet Aslan, he greets Peter first, then sends Susan and Lucy off to get food. Aslan then invites Peter to see the castle where he will be king, before revealing that Peter will be the “High King over all the rest”. There is no explanation provided for this. Peter, being the oldest, and being a male, must simply be the most important character (let us not forget that Lewis wrote this book for his goddaughter).

Also, Father Christmas is in this book for some reason, and when he arrives out of the blue, he gives the children gifts. Peter gets a shield and sword, Susan gets a bow and quiver full of arrows (which I always thought was pretty cool as a kid), and Lucy gets a bottle full of magical healing potion and a dagger. However, Father Christmas makes it very clear that he does not mean for the girls to be involved in any battles, because “battles are ugly when women fight”. After dropping these words of wisdom, he sleds off and is never seen again.

When Lucy and Susan get attacked by wolves later in the story, both run away (understandable), and Susan climbs a tree. But instead of firing an arrow at the wolf, Peter sees that she is “just going to faint” (the word “just” here making her seem even more pathetic). At no point in the book does Susan get to use her bow and arrows to defend herself. But Peter gets to use his sword. He kills a wolf with it, and later on, he even manages to fend off the White Witch, despite her being established as being half-giant. You see, Peter has the ultimate super-power: being male.

Inherent behaviours?

I’ll mention this quickly, although it remains a thorny issue in fantasy and science fiction to this day: when you have multiple species with human-level intelligence in your fantasy world, is it acceptable for them to have inherent traits associated with their species? Are orcs always aggressive? Are elves inherently clever? Different writers handle this in different ways, with modern writers more aware of the parallels that might be drawn between fantasy people and real-life prejudices. Obviously, C. S. Lewis was writing well before anyone was worrying about that. And this leads to some interesting decisions regarding the behaviour of different species.

In Narnia, any species that “looks human but isn’t” is treated with great suspicion. Dwarfs and giants are listed as prime examples of untrustworthy species when Tumnus explains this concept to Lucy. He doesn’t explain why this is the case; we are simply informed that these species are inherently prone to evil. Later, they meet a giant called Rumblebuffin, who is evidently very friendly. However, Tumnus explains that the Buffins are a “an old family” with “traditions, you know” and implies that the “other sort” are the ones to watch out for. He seems to suggest that good giants are the exception to the rule – and this didn’t sit well with me, for hopefully very obvious reasons.

At no point does Lewis dwell on this issue, because it is clear that he didn’t regard it as an issue in the first place. When the children are crowned kings and queens of Narnia, they make it their mission to exterminate all evil creatures from the land, until “that foul brood” is “stamped out”. The suggestion is that every creature that followed the White Witch was inherently evil, and could never repent. Which feels like an odd message for a book that keeps trying to teach me Christian values.

We need to talk about Aslan.

We have established that Aslan is the Jesus of Narnia. He is the son of God, which, if I am not mistaken (I probably am) makes him God as well (sort of). He is an all-powerful being, who cannot be killed. And this is problematic from a narrative standpoint.

The children in this story (except Edmund) don’t have very much agency because Aslan does all the hard work for them. Right at the start of the book, Tumnus explains that the White Witch will be defeated when “the four thrones at Cair Paravel are filled”, so it is obvious that this is where the four children will end up. Any kid might think that our four protagonists would have to defeat the White Witch in order to get there – but no. When it comes to the battle, Aslan runs in, jumps at the White Witch and kills her instantly. Peter was fighting her, yes, and Edmund apparently broke her wand, but all of that was meaningless. She is killed by Aslan in a second, the moment he puts his mind to it.

Aside from Edmund, the children never show any desire to be rulers of Narnia. It is expected of them – forced upon them, even. Aslan tells Peter that “he must sit as king” – suggesting that Peter has no choice in the matter. The end of winter just… happens. Apparently this is because Aslan has come back, but we never really find out. And after the battle, the four children are made rulers, despite having not proven themselves in any meaningful way. They have arrived in Narnia only days before, in a place where humans are regarded as an exotic species, and for some reason, the animals and beasts are happy to have them as rulers? The Christian hierarchy is at play again here, and it feels decidedly shallow.

My final question about Aslan (and this is a big one) is whether he walks on four legs or two. From what I can gather, he does a bit of both. Clearly, when he runs, he runs on four legs. But when he addresses the creatures, he “shook his mane and clapped his paws together”, and when he is talking to Peter, he “laid his paw on Peter’s shoulder” – which would only be possible if he was standing on two legs. Like a man. Like Furry Jesus.

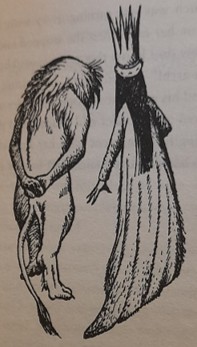

This was not a mental image I needed. And it was solidified, with perfect timing, by this wonderful illustration by Pauline Baynes:

Finally… It’s very stupid to shut oneself in a wardrobe.

Every time any of the children climb inside the wardrobe, Lewis makes it very clear that shutting yourself inside a wardrobe is a very stupid thing to do. The only one who closes the door behind them is Edmund, in yet another display of pure idiocy. Legend has it that Lewis included these remarks upon being told that, after reading his books, children might get themselves locked inside wardrobes. So you must never shut the door behind yourself, understand?

In summary…

I still like The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and I can see why I enjoyed it as a child. As an adult, however, the book is fascinating on a whole new level. The world-building may not be as leak-proof as other works of fantasy fiction, but children are generally less pedantic than adults… And the magic of the lone lamppost, standing in the middle of a snowy forest, cannot be denied.

I think the real winner here is the wardrobe. Using an ordinary piece of furniture as a portal, connecting the real world to the fantasy world, was a genius plot device. Even if Narnia lacked a comprehensive back story, a believable ecosystem, or anything for Susan to do, the premise that a fantasy realm might exist in the back of your wardrobe sells the idea to children almost instantly. The connection to the real world makes Narnia tangible and believable, even for a child who doesn’t have the necessary doctorate in medieval studies to understand half the creatures that Lewis included.

I’m going to read Prince Caspian next, continuing in the order that Lewis wrote the books. From what I remember, we see a bit more character development from the four children, and get a little bit of political scheming thrown into the mix. I get the feeling that there will be plenty to talk about.

Happy reading, and have a lovely week!

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) is weirder than I remembered”