Hello readers! It’s time for another deep-dive into the Chronicles of Narnia. Last time we discussed The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, which was the first book in the series to be published; this time we will discuss Prince Caspian, which released just one year later, in 1951. I remember preferring this story as a child, as it had a grander sense of adventure – so I was keen to pick it up again, to see if my perceptions had changed. The first book was a lot stranger than I remembered, with Christian overtones that I had overlooked when I was younger, and I wondered whether Prince Caspian had the same issues.

The title of this post sums up my feelings. Prince Caspian was nowhere near as exciting or adventurous as I remembered. The parts of this book that I enjoyed as an adult were the same parts that I remember loving as a child, but these are scarce. There is a lot of fluff in this book, and there are some sections that feel decidedly out of place. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. First, I’ll provide a quick overview of the plot…

SPOILER WARNING!

There will be major spoilers ahead. But if you didn’t read this book as a kid, do you mind the plot being spoiled for you as an adult?

Plot summary

The story starts with a paragraph summarising the events of the previous book, reminding us that Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy had been kings and queens of Narnia. They had grown into adults in the magical realm, but when they accidentally returned to our world, they all reverted to children, and discovered that no time had passed since they had entered the wardrobe. Lewis states that this all happened one year ago. The children are now on their way back to boarding school, and they are waiting at a railway station feeling very gloomy.

Suddenly, all four of them are pulled back into Narnia (no wardrobe necessary). The station vanishes, and they find themselves in a dense woodland, which they struggle through to reach a calm, sandy beach before a dazzling blue sea. They splash around for a while, then go to explore – only to realise that they are on an island, separated from the mainland by a narrow channel. They discover some ruins, which they recognise as Cair Paravel, their castle in Narnia. Far more than one year has passed since they were last here; the walls have crumbled, the peninsula has become an island, and the forest has grown dense and dark.

The children find the treasure room, and recover the gifts that they received from Father Christmas in the previous book. Peter reclaims his sword and shield, Susan reclaims her bow, and Lucy reclaims her healing potion (Edmund gets nothing, because he was too busy being an evil backstabber to meet Father Christmas). However, Susan’s horn, which can summon magical help, is missing.

The next day, a boat appears, rowed by two soldiers. They have tied up a dwarf, and plan to drop him into the sea to drown him. Susan fires an arrow at their helmets to scare them off, and the children rescue the dwarf, who tells them that Narnia is in the grip of a civil war. There follows several chapters of backstory…

Lewis now tells the story of Prince Caspian, who was raised by his uncle, Miraz, King of Narnia. Caspian and the other humans in Narnia are from the land of Telmar, and are known as Telmarines. His nurse tells him about the “old days” when animals could talk, but Miraz tells him that this is nonsense, and sends the nurse away. Caspian gets a new tutor, Doctor Cornelius, who informs Caspian that all the old tales are true, but that Miraz refuses to acknowledge the existence of the “old Narnians” – the centaurs, dwarfs and giants who lived there before the Telmarines invaded.

As Caspian grows up, he realises that Miraz is cruel, and that the people of Narnia are unhappy because of high taxes and harsh laws. He learns that Miraz murdered his father, and that he should be king – but Miraz has usurped the throne, and killed off any lords who might have supported Caspian. One night, the queen gives birth to a son, and Caspian is forced to flee, terrified that Miraz will kill him. His tutor gives him Susan’s horn, “the greatest and most sacred treasure of Narnia”.

A storm descends, and Caspian’s horse bolts in terror. He hits his head on a branch, and awakes to find himself in a cave, being looked after by two dwarfs, Nikabrik and Trumpkin, and a talking badger named Trufflehunter. We learn that the old Narnians are keen to have a rightful human king, but some of them (particularly the dwarfs) have lost faith in Aslan. Nikabrik makes it clear that he will follow anyone who will drive the Telmarines out of Narnia, whether that is Aslan or the White Witch.

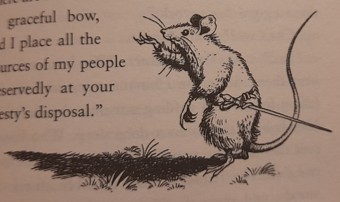

Caspian goes to meet a long list of animals and creatures, including bears, dwarfs, fauns, centaurs, and the sword-wielding mouse Reepicheep. However, Doctor Cornelius warns that Miraz is coming to eradicate them. They head to Aslan’s How, an earthen mound constructed by old Narnians to protect the Stone Table. Caspian and his ragtag army defend it as best they can, but they are out-numbered and out-strategized. In desperation, Caspian blows Susan’s horn – which summons Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy back to Narnia.

The story returns to the children, and we learn that the dwarf they rescued is none other than Trumpkin. They head into Narnia, following the river. However, the landscape has changed in the centuries since they were last there, and they get hopelessly lost. Lucy suddenly sees Aslan in the trees – but none of the others believe her. Instead of going towards him, they carry on up the river, and end up getting shot at by soldiers, and forced to retreat. That night, Lucy sees Aslan again, with tree spirits dancing around him. He says he will guide them, but the others may struggle to see him at first; they must put their faith in him, and in Lucy.

Lucy convinces her siblings to follow her, and Aslan guides them to Prince Caspian. Along the way, all of them start to see him, and they apologise to Lucy for not believing her (again). Aslan wakes up the trees, and sends the boys ahead.

The boys and the dwarf arrive at Aslan’s How, where they hear Nikabrik introducing Caspian to a hag and a werwolf who want to bring the White Witch back from the dead. Trumpkin runs in and beheads the hag, and the lamp blows out; when it is relit, they see that Nikabrik and the werwolf have been killed in the scuffle. Peter takes control, and challenges Miraz to single combat in order to end the war without further casualties. Miraz agrees, and the pair of them fight to the death.

The book gets a little dark at this point, when you consider that Peter is just a child – probably in his early teens at most. At one point he openly admits that he expects to die, and even says “so long, old chap” to Edmund. Thankfully, Miraz trips and falls – and when Peter holds back from killing him, Miraz is killed by one of his own treacherous lords. There follows an all-out battle, which the Narnians win at the last minute due to the forest coming to life and chasing the Telmarine soldiers away.

Meanwhile, the girls and Aslan are wreaking havoc elsewhere. Aslan is destroying bridges and buildings with vines, restoring the wilderness to Narnia, and recruiting the worthy from the wreckage, while chasing away the unworthy.

Finally, with the battle over and Narnia returned to the old Narnians, Aslan reveals that the Telmarines came to Telmar from our world, and that he intends to send them back through a portal. Apparently, their ancestors were pirates who became stranded on a desert island and made the natives their wives. Some of them found a cave on a mountain at the top of the island, and fell through into Telmar, then filled the land with their descendants.

The Telmarines are reluctant to go through Aslan’s portal, so Peter says that the four children should go through to demonstrate that it is safe. They go through – and that’s it! They appear back on the railway platform, and the story ends.

My initial thoughts

This book has a lot going on, because we have Caspian’s story as well as the adventures of the four children. However, due to the constraints of this being a short children’s book, both of these stories feel somewhat underdeveloped. I can see why elements of this tale appealed to me as a child; the discovery of the Cair Paravel ruins, Caspian’s backstory, and the single combat were the parts I remembered. However, there are other sections that feel extraneous or list-like, which I had completely forgotten, and which made the pacing feel quite inconsistent.

First, some historical context…

Lewis actually finished Prince Caspian in 1949, before The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was published. So, he wrote this sequel simply for his own enjoyment, rather than in response to his first book’s success. It also means that he hadn’t received any feedback from readers – which is worth bearing in mind as I pick apart some key themes.

The children have no common sense

Perhaps this is a silly complaint, given that children have half-formed brains, but I still found some of their reactions to events quite unconvincing. For example, when they first appear on the beach, none of them panic. They all tear off their shoes and socks and go to splash in the water. Why aren’t they terrified?! They have been abducted by magic! Only a while later do they start worrying about being stranded on a deserted beach, with only two sandwiches to sustain the four of them, and no fresh water.

Then, when they arrive in the ruined castle, they don’t recognise it as their castle. How could they not recognise it?! They lived in Cair Paravel for years! Peter merely remarks that “it is the queerest thing that has happened this queer day” and it takes Susan finding one of their old chess pieces for them to figure it out. Where did they think they were?!

I thought that the children had some odd reactions in the last book, too. For example, none of them were alarmed by a talking beaver. And Edmund wasn’t the least bit scared of a witch who was half-giant. This is in stark contrast to Caspian, who is absolutely terrified when he awakes to find a giant talking badger looking after him. This is the reasonable reaction! Why does Caspian behave normally, but the four main protagonists don’t?

The psychological damage of reverting to childhood

Another huge issue throughout this story, set up at the end of the last book, is that the four children lived adult lives in Narnia before returning to the real world and reverting to children. All of them carry adult memories in their heads – so technically speaking, they are twenty or thirty years old, but in the bodies of children. Which is deeply unsettling.

Lewis states that the children never spoke of their lives in Narnia to anyone except “one very wise grown-up” (the professor from the last book), which neatly avoids the scenario in which they were locked up in mental asylums. But why would they keep it a secret? How on Earth could they cope with their sudden return to the bodies of children? It isn’t as if they forget their adult lives in Narnia; throughout Prince Caspian, they tell stories of their adult adventures.

In the last book, Lewis establishes that, as kings and queens, they entered alliances with countries beyond the sea, and that Susan received many marriage proposals. When they return to Narnia, Peter recalls “the day before the ambassadors came from the King of Calormen” and “the great Tournament in the Lone Islands”. When Edmund challenges Trumpkin to a swordfight, “all his old battles came back to him, and his arms and fingers remembered their old skill”. Later, when Lucy looks up at the stars, she remembers that “she had once known them better than the stars of our own world, because as a Queen in Narnia she had gone to bed much later than as a child in England”.

These children lived as adults. They had their adult lives stripped away from them without warning, and they still remember everything that happened. It’s about as psychologically messy as you can get! Susan gets upset when she finds the chess piece and remembers the old days, but this is the only time that any of them show any emotion besides excitement regarding their experiences. How have none of them spiralled into depression or psychosis?!

As a final note, I’ll refer back to my previous point: the strange decisions and reactions of the children make even less sense when you consider that they possess the wisdom of adults.

Were there always other humans in Narnia’s universe?

Throughout the last book, it was stated time and time again that there were never any humans in Narnia. This was why the creatures were so surprised to see the children when they arrived. However, Lewis never established whether there were nations with human populations in the same universe as Narnia. When Peter talks about ambassadors from Calormen, or a tournament on the Lone Islands, or when Susan received marriage proposals, did these involve humans – or mythological creatures?

When the children see two soldiers rowing a boat near the ruins, none of them points out how strange it is to see other humans in Narnia. I suspect that this might be an oversight on Lewis’ part – but perhaps humans became a common sight in Narnia, later in their reign?

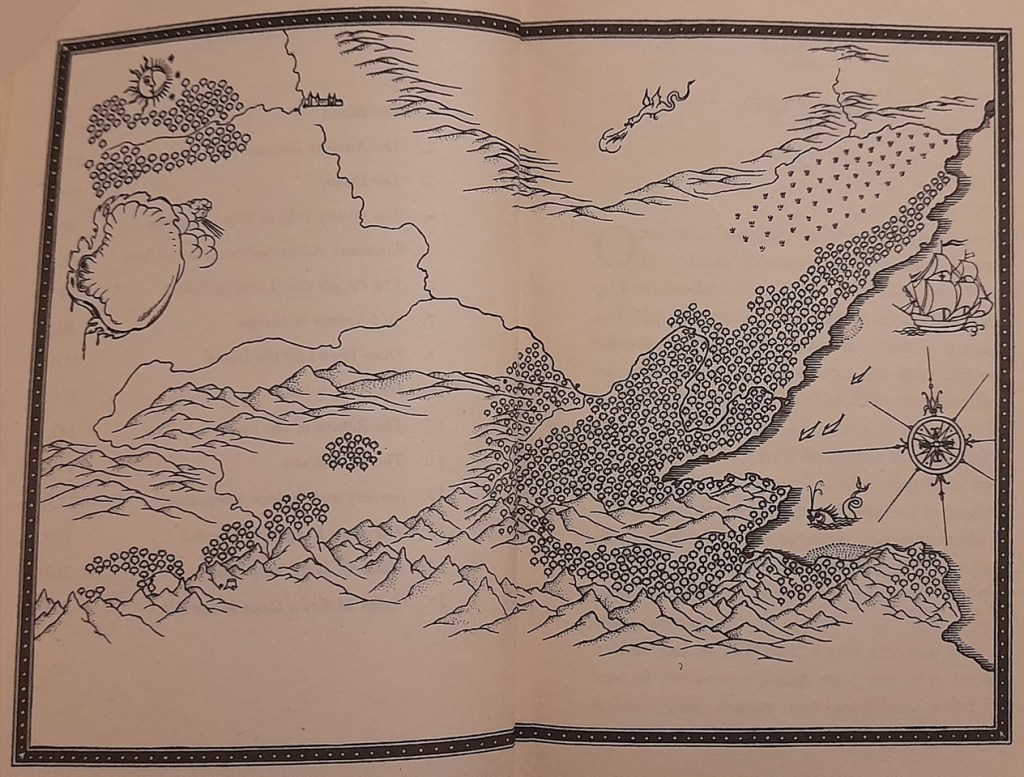

In Prince Caspian, Lewis names even more nations. Telmar is stated to exist beyond the western mountains, and Doctor Cornelius instructs Caspian to head south, “to the court of King Nain of Archenland”. The book even has a map on the first two pages – although I must say, it’s not an inspiring map by any means. It has no border or settlements, and the rivers don’t line up with the mountains in a geographically robust manner. None of the nations mentioned in this book are labelled. And considering that the last book didn’t have a map, we can’t even ascertain the landscape changes wrought by time.

Edmund is still obnoxious.

““That’s the worst of girls,” said Edmund to Peter and the Dwarf. “They never carry a map in their heads.”” This line speaks for itself. I genuinely remember getting angry over this as a child. Also, Edmund insists on calling Trumpkin the dwarf “Dear Little Friend” which he abbreviates to DLF. This is used by the boys for the rest of the book, despite Trumpkin’s protestations. What humorous banter.

The gendered adventuring persists

The activities of the girls and boys are very clearly defined, with the boys given active roles, and the girls almost always given supporting roles. For example, when they first find the ruined castle, the boys set about lighting the fire, but the girls go to pick apples for their dinner. There is no discussion about this; the girls know their place.

When it comes to figuring out what is going on, only Peter and Edmund have anything useful to say. It is Peter who realises that they are in the ruins of Cair Paravel, and it is Edmund who proposes that time flows differently in Narnia than in the real world. The girls just take a back seat, and interject with questions when the time is right.

If ever the girls get slightly close to combat, they are utterly useless. When they are shot at by Telmarine soldiers, Trumpkin pushes Lucy down, and Peter pushes Susan down, as if they wouldn’t have had the sense to seek cover for themselves. Neither of the girls are present when their brother is fighting Miraz to the death, even though Lucy has the one magical healing potion that could possibly save her brother’s life. But oh no – they couldn’t possibly be near such a testosterone-fuelled activity.

And a final amusing quote: “Peter leaned forward, put his arms round the beast and kissed the furry head: it wasn’t a girlish thing for him to do, because he was the High King.” Thanks for clarifying, Lewis. I was worried for a moment there that Peter accidentally transitioned by kissing a badger.

We need to talk about Susan.

Remember that Lewis finished this book before The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was published. So he had yet to receive any letters from disgruntled little girls asking him why Susan was such a useless role model. In Prince Caspian, Susan is a little bit more involved, which would suggest that Lewis had some self-awareness regarding his passive sexism; however, there are also some very clunky attempts to insist that Susan is an interesting character, which feel as if they were tacked-on at the last minute.

At one point, Lewis states quite bluntly that “archery and swimming were the things Susan was good at” – and he has to state it bluntly, because we have yet to be provided with any evidence that she can do either of these things. When Peter suggests that Susan could swim to the mainland, Lewis even includes a bracketed acknowledgement that “Susan had won prizes for swimming at school”. She is accomplished, you understand. Don’t be thinking that Susan is a wet blanket.

In the last book, Susan was given a bow and never used it – not even to defend herself from an attacking wolf. This time, she gets to fire a few arrows, although never in combat. When she fires a warning shot at the helmet of the soldier, she insists that she “wasn’t shooting to kill”. Honourable sentiment, I suppose. But later, she fails to shoot a bear that is attacking Lucy, because she is worried that it might be a talking bear. If Trumpkin hadn’t shot it himself, Lucy would be dead because of Susan’s inaction. She’s still just useless.

Throughout the book, Susan complains and grumbles. When the boys find the door to the treasure room, she pleas with them not to break it down until morning, because she doesn’t want to sleep with an open door behind her. When they head north, she even hits them with “I knew all along we’d get lost in these woods” despite having done nothing to help with the navigation (neither of the girls try to navigate at any point, because, as established earlier, they are unable to carry maps in their heads). When the boys skin the dead bear, Susan takes Lucy away so that she won’t see it. And finally, when Lucy tells her about Aslan, Susan uses “her most annoying grown-up voice” to tell her she is dreaming. This line is particularly telling; Lewis is writes more favourably of Lucy, who is still a girl – but Susan, who is practically a grown woman, is treated with more disdain.

The racism is more explicit

Oh, you thought we were done with analysing Lewis’ prejudices? Absolutely not.

The two dwarfs in the tale are of two different races: Nikabrik is a “Black Dwarf” and Trumpkin is a “Red Dwarf”. Lewis adds clarification (in brackets) that a “Black Dwarf” is black because “his hair and beard were black and thick and hard like horsehair”, and that a “Red Dwarf” is red because he has hair “rather like a Fox’s”. It is strongly suggested that the black dwarfs are inherently evil, and that the red dwarfs are generally more benign.

Nikabrik has an evil temperament from the start. He reveals that he hates “renegade dwarfs” (i.e., half-dwarfs) like Doctor Cornelius “worse than humans”. And of course he is the one to befriend the hag and the werwolf. Later, we learn that “Nikabrik was not a smoker” – as if this is an unarguable indication of bad character.

The decision to assign inherent traits to particular species is a thorny issue in the fantasy genre. However, I feel that Lewis has taken this to another level by attributing an inclination for evil deeds to a particular race. Should we still be reading this to children? Maybe only with adult supervision.

We learn more about the Narnia ecosystem

In Prince Caspian, Lewis explains that there are talking and non-talking animals in Narnia – a distinction that was missing from the last book. Trufflehunter tells Caspian that most of the animals in modern Narnia are “different” from the talking creatures; indeed, we meet talking bears who fight for Caspian, and encounter a non-talking bear which attacks Lucy. Trufflehunter explains that these animals are like the “dumb, witless creatures you’d find in Calormen and Telmar” – suggesting that the talking animals of this universe live only within Narnia. We also learn that the talking animals are larger than their mute counterparts; when we meet Reepicheep, Lewis explains that he is “bigger than a common mouse, well over a foot high when he stood on his hind legs”.

You might remember that in the previous book, a group of ordinary mice chewed through Aslan’s ropes, setting him free. In Prince Caspian, Aslan reveals that mice only became talking animals in reward for their efforts – which makes me wonder whether all of the animals had to earn their right to speak, or whether this is just Lewis correcting an oversight from the previous book.

Things get weird again…

After the children meet Aslan and he wakes up the trees, people emerge from the forests. One of these is an old man on a donkey, and one is a wild young man chased by lots of dancing women. Lewis states that the old man is Silenus and the young man is Bacchus – both from Greek mythology. Bacchus is otherwise known as Dionysus, the god of wine and male fertility (amongst other things), and Silenus is his tutor, eternally drunk. Indeed, when they appear in Prince Caspian, Silenus yells about “refreshments” and the landscape becomes swamped in vines and grapes. Their appearance feels very, very out of place – especially in a children’s book! And they aren’t just cameos; the vines are crucial in pulling apart Telmarine settlements and bridges, cutting off the soldiers’ escape.

Some descriptions have NOT aged well

When Aslan is chasing away the Telmarines and returning the wilderness to Narnia, he destroys several towns, and levels multiple buildings, including schools. At the girls’ school, only one of the girls is happy to join Aslan, and the others who run away in fear are described as “mostly dumpy, prim little girls with fat legs”. This description came out of nowhere – and I don’t see what legs have to do with faith in Aslan. Why was Lewis even thinking about girls’ legs? At the boys’ school, Aslan invites a beleaguered young teacher to join him, and turns her entire class into piglets. Is this really what furry Jesus would do? Condemn young children to become bacon butties? It doesn’t seem very forgiving.

This book is very violent at times!

For the most part, Lewis seems to remember that this is a book for children, and avoids describing any grisly injuries. When Peter fights Miraz, the action is conveyed through the commentary from Edmund and Doctor Cornelius, rather than describing the fight itself. Until this point, none of the children have been reported to have killed anyone – especially not another human. For most of Prince Caspian, they avoid conflict; Susan only fires warning shots (or not at all), and only Trumpkin gets his hands dirty with killing the bear. So, I was interested to see whether this pacifism could survive the single combat.

The fight ends when Miraz trips and falls, at which point two of his lords jump into the ring and stab him in the back. I assumed that this was Lewis contriving a way to keep Peter’s hands clean, but no; in the very next line, Peter chops one of the lords’ legs from under him, then chops off his head on the back-cut from the same stroke! He kills a grown man – a human man – in a children’s book! I understand that this lord was a bad guy, but still!

Are the Telmarines the bad guys?

We get very mixed messages throughout this book regarding the Telmarines. Lewis implies that there are many of them living in Narnia, in a feudal society, so we can only assume that most of these people are peasants, living peacefully. Early on, Caspian learns that the people are unhappy due to Miraz being a cruel ruler – but later, we see the Telmarine soldiers fighting for their king, cheering him on. Which is it? Do they hate him? Do they not?

At one point, the children are shot at by Telmarine soldiers – which had me absolutely baffled. Why would human soldiers fire at human children? It makes no sense. The Telmarines only consider the talking animals and mythical species to be their enemies; they would consider other humans to be their allies. And why fire on children?! That’s crazy.

Later, the soldiers cheer for Miraz as he fights Peter, which again feels very odd. Peter is a child, maybe in his early teens. Why would the soldiers possibly root for Miraz, a leader who they reportedly hate, when Peter is the obvious underdog? The fact that Miraz has agreed to fight a child in the first place should lose their respect. Their reactions make no sense. Lewis can’t seem to decide whether the Telmarines are ordinary people or inherently bad guys; when Aslan arrives, he treats most of them like lost causes. Again, this feels tonally wrong for a novel which, on the surface, boasts such Christian values.

A final complaint about pacing

This book fizzles out rather than ending. With only a few pages left, Lewis introduces two new characters, the Telmarine lords Glozelle and Sopespian, who have an extended discussion with Miraz to persuade him to accept the fight with Peter, knowing that he will lose. Their political scheming takes longer than the fight itself – and we gain virtually nothing from it, given that Peter kills them on the next page. The battle is also over very quickly, and once it ends, Lewis spends multiple pages describing the celebratory feast, even providing a long description of the types of earth eaten by the trees.

At the end of the book, Caspian is made king, having done virtually nothing to prove himself worthy. Just like in the previous book, the fight was won by Aslan, and the children were just there to watch it happen. This is probably why the pacing feels wrong – there just isn’t any payoff. The adventure ends rather abruptly.

In summary…

I hope you enjoyed the second deep dive into Narnia! I was surprised by Prince Caspian; I thought it would hold up better than it did. Next up is The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, which was also written before The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was published, and before Lewis had received any audience feedback. I don’t remember being too fond of this entry, but I’m more than happy to be proved wrong.

Happy reading, and have a lovely week!

In case you missed the last Narnia post:

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.