Hello readers! It’s time for the second instalment in this series of six-minute summaries. Last time, we covered Alfred Wegener, who brought about a paradigm shift in the Earth sciences with his idea of continental drift. This time, we’ll look at another revolutionary thinker: Florence Nightingale. International nurses day was on Friday 12th May, which – by complete coincidence – was the day I started researching this blog. I could pretend that writing a timely six-minute summary was always my intention, but no: this was either divine intervention, or just a 1-in-365 chance event. The universe works in mysterious ways.

The lady with the lamp

Florence Nightingale is most famous for being a nurse in the Crimean War, where she improved hospital standards and saved countless lives. In fact, she is often regarded as the inventor of modern nursing, and international nurses day is celebrated on her birthday. Soldiers called her the “lady with the lamp”, as she would patrol the hospital wards by night, watching over the wounded. This romanticised image of her as a guardian angel is the one which has stuck in our cultural memory, allowing Florence Nightingale’s greater achievements to fall into obscurity. She was more than an ethereal, lamp-wielding presence. She was a social reformer – and a statistician.

A statistician?

There has been a growing effort in recent years to rectify our collective memory of Florence Nightingale. If you start typing her name into Google, it suggests “Florence Nightingale: English statistician”, while Wikipedia describes her as a “social reformer, statistician and founder of modern nursing”. Clearly, there is more to Florence Nightingale than hospitals in Crimea. And she was certainly more than just a nurse with a nightlight.

A brief history

Florence Nightingale was born in 1820 in the city of Florence, to English parents with an apparent lack of imagination for baby names. Her older sister, Parthenope, suffered the same treatment, having been named after a lesser-known part of the city of Naples. Still, whatever the Nightingales lacked in imagination, they made up for in inherited wealth. When they returned home with their two daughters, finally ending an egregiously extended honeymoon, they lived in a big house called Embley Park, a place so ostentatious that it has now evolved into a £12,000-per-term boarding school.

When she was in her late teens, Florence believed she received a call from God, telling her to be a nurse – a recruitment strategy that would probably work wonders for our NHS today. However, Florence Nightingale’s parents were not keen on her career aspirations. They thought she should be getting married and going on extended honeymoons around Europe, popping out babies like a Pez dispenser. In their view, nursing was beneath her, no matter how many times God said otherwise.

However, Florence’s rebellious ambitions shouldn’t have come as a surprise to her parents. They had made the unfortunate error of educating her, allowing her to become proficient in French, German, Italian, Greek and Latin, and letting her excel in mathematics, of all things. She refused to give in to societal pressures, and she was thirty by the time her father finally gave her permission to do as God said and train as a nurse. Her determination certainly paid off. By the time she was thirty three, she was working as the superintendent in a hospital in London, proving to her parents that they should never have doubted the career advice of an omniscient deity. However, it was the outbreak of war in Crimea in 1853 that really gave Florence the chance to shine.

The lamp-wielding era

Although the war was fought in Crimea, the wounded soldiers were taken to hospitals in Istanbul, and this was where Florence Nightingale worked. News of the terrible conditions had made it back to Britain, and the government was under pressure to fix things. So it was that Florence Nightingale was sent out with 38 nurses, who were put in charge of basic care such as changing dressings, cleaning the wards, and providing food.

As much as the press tried to present Florence Nightingale as a miraculous guardian angel, what she really did was shine a light on poor practise. While she worked, she kept a meticulous record of the causes of deaths, allowing her to identify the various shortcomings within hospitals, and to target particular areas for reform. Most importantly, the collection and presentation of data allowed her to demonstrate the existence and the extent of problems to politicians, leading to significant improvements in care.

The power of statistics

The reason that Florence Nightingale was so effective at reforming hospitals is because all her decisions were evidence-based. She collected data in order to find the root of problems, and so that she could argue her case when it came to solving them. Without the data to substantiate her assertions, her recommendations may well have been ignored. The opinions of a woman in the medical profession would have meant less than those of a male doctor – and so she had to have the numbers to back her up.

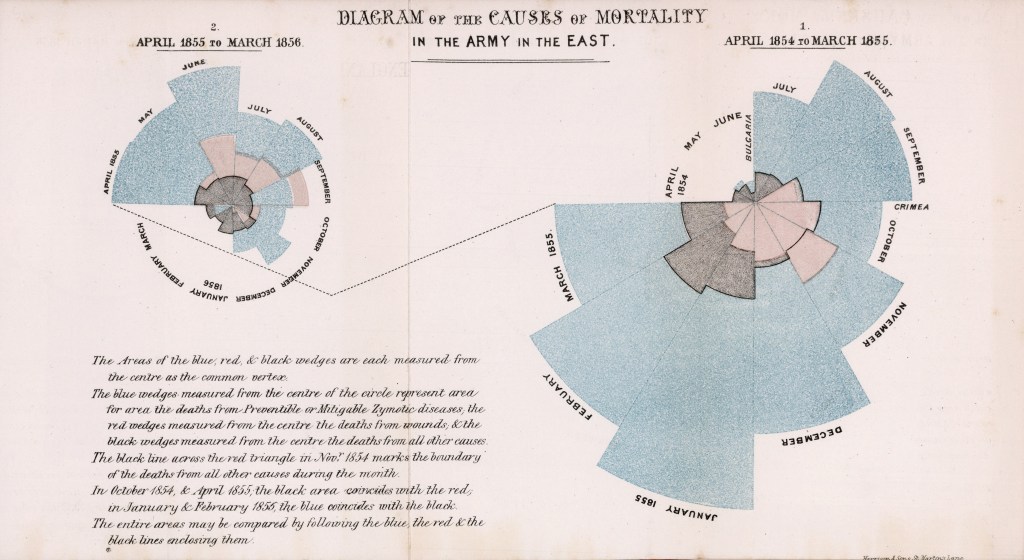

However, data collection was only half the battle. Florence Nightingale knew that to convince innumerate politicians of the existence of a problem, she would need to communicate complex concepts rapidly and effectively. To achieve this, she used various types of graphs and charts. Many of these we now take for granted – like pie charts, for example – but they were relatively uncommon at the time. Most famously, she used a radial polar histogram to show how the causes of death varied throughout the year, as shown below.

This type of chart is sometimes called a Nightingale rose diagram in her honour. It is likely that she came up with the concept independently, although a couple of examples had been drawn up by French statisticians a few years earlier. Even if she didn’t truly invent it, she certainly popularised it, and it remains a valuable tool for the presentation of circular data (e.g., the months of the year, or angles 0-360).

Against the odds

Florence Nightingale’s social and medical innovations were revolutionary, and this was very much recognised at the time. She was the first woman to be awarded the Order of Merit, and the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society. However, it is worth noting that most of her reforms would not have been possible had she not already known some of the most powerful people in the land. She came from a wealthy background, and counted many politicians as friends; for example, she met the secretary of state for war while on holiday in Rome, and when the Crimean war broke out a few years later, he was the one who authorised her to improve the state of military hospitals.

In no way do I want to belittle Florence Nightingale’s achievements. She brought improvements to nursing and sanitation that saved countless lives, and was a pioneer in evidence-based policy making. It is only a sad reflection on the nineteenth century that who you knew mattered more than what you knew, and that women could only attain positions of power and influence if they had the money to do so, as well as the bravery and stubbornness to reject societal pressures.

I only mention these issues because I wonder how many of them remain in the modern era. It is still true that coming from a wealthy background provides more freedom to pursue your interests and educate yourself. It is still true that the upper classes exert disproportionate control over government policies. It is also still true that women face barriers in the field of science and statistics. All of these are known issues, of course, and progress is being made – but while these additional hurdles exist, who knows how many potential Florence Nightingales might be lost to us? Had she been any poorer, or any less educated, she may never have wielded that lamp in the way she did – even if she had the potential to do so.

Some nuance

One final point worth making is that Florence Nightingale nurtured some outdated and unsavoury opinions. She published hundreds of articles throughout her life, most of which are now in the public domain, but her more questionable views are usually overlooked whenever we celebrate her achievements. In a time of British colonialism, she viewed the expansion of the empire as a force for good, bringing cleanliness and civilisation to the people and cultures it overpowered. For example, she played a major role in improving sanitation in India, and while this is typically celebrated as a success, her language and attitude would not be acceptable today.

She also had some questionable views on women, with a particularly spicy letter in 1861 claiming that women “cannot state a fact accurately to another, nor can that other attend to it accurately enough for it to become information”. It’s fascinating to me that she considered herself superior to other women, and perhaps not even as a woman at all – in fact, she would refer to herself as a “man of action”. This mindset could warrant a whole blog post all to itself, as she clearly believed in gendered roles, but distanced herself from them in order to achieve her aims. A woman, yes – but not like all the others.

(Note: this is only my first impression. There is a lot more to this than a few hours of research can unearth – and it needs more than six minutes to discuss the complexities.)

Six minutes over!

Florence Nightingale was certainly an interesting figure. It is very common to see her name memorialised around the UK, but many of her achievements remain unknown. The next time you see a radial polar histogram, remember who popularised it! And if a god calls and recommends that you become a nurse, maybe take their advice.

Discover more from C. W. Clayton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.